Chapter 10: An Outstretched Hand [Part 2]

It was an ancient Roman idea — the octagon.

The building that would later be called the Baptistery of San Giovanni, had been raised when Florence was but an infant herself. Its shape was a kind of sacred geometry, neither a rigid square, belonging to the earth, nor an eternal circle, for the endless heavens — but a bridge between the two.

As the centuries turned and the theatres fell silent, the bathhouses gathering weeds, the aqueducts cracked and turned dry. The Christian church came upon her then — a cracked shell amid broken arches and scattered stone. They found her shape pleasing, for it could be turned to their purpose. They bound the form to their own story: seven days to make the world, and an eighth for rebirth.

Because nothing is ever so final that it cannot be reclaimed, nothing so fixed that it couldn’t be turned to another purpose.

The crowd presses in through the Baptistery doors.

Outside, voices still carry across the square, but once the threshold is crossed, reverence steals their tongues. Grey morning light falls away as they shuffle forward, a tide of townsfolk drifting into the dim hall, footsteps smoothing across worn marble. For a moment the chamber is swallowed in shadow, only the rustle of fabric, whispers sinking low — then the sudden screech of benches dragged across stone, echoing upwards like startled birds into the vault above.

Matteo follows close behind the broad shoulders of his father, as the column sways out into the hall, snaking into rows of waiting benches to left and right. He breathes the rich spice of incense, its perfume long steeped into the chamber itself.

Ahead, marble pillars rise to frame a marble dais, raised beneath a wide canopy, all hewn from stone. Tall-backed seats of carved walnut are pressed shoulder to shoulder, in row upon row, inlaid with velvet cushions of deepest crimson waiting expectantly for the judges to arrive.

Brunellesco moves to take his seat, using a hand to steady himself, but Matteo stands a moment longer, tilting back onto the edge of one heel, pivoting slowly anticlockwise, his gaze sweeping the hall. Along the northwest wall, a neat row of seven guilded panels catches what little light there is. Clustered before them, murmuring and nodding, capped heads tilt from one scene to the next — one more golden surface beneath a mosaic sky.

To the left, Matteo sees his brother. Filippo is being herded toward the front row to where the other contestants sit apart, halfway between the audience and the dais. His boots drag on the marble like a reluctant mule as a young usher urges him on. And Lorenzo, patting the empty seat beside him, grinning at Filippo’s unease.

Still turning, and Matteo’s chestnut eyes reach the chamber’s angled edges, where the women and children are pressed to the patterned walls, and receding between stone pillars. Mothers balancing babes upon their hips, whispering to keep them still. Matteo scans their faces, pale ovals in the dim light, and catches sight of his mother just as the great doors beside her groan shut with a sonorous boom, sealing them all inside.

The square outside is left empty now, the townsfolk drawn within.

Two buildings remain, regarding one another across the cobbled square, long companions. The Baptistery of San Giovanni, compact and octagonal, and the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore towering above it, her unfinished drum piercing the sky. Both clad in the same Florentine skin of white and green, their patterned stone dulled beneath their blanket of grey.

Between them, cobblestones darkened by damp, reflect the shifting light. Shafts of sunlight break through the cover, and the clouds begin to thin and loosen, revealing patches of pale blue sky.

At the end of the hall, the north doors groan, creaking open on ancient hinges. A wash of daylight slips across the dais where carved chair legs had cast their long black shadows only moments before. From the distance comes a bright staccato, heels striking stone in crisp succession, gowns on a train of fresh-shone shoes as the jury files swiftly in.

They are led by two of the Priori of the Signoria cloaked in robes of crimson, followed by stern-faced men wrapped in velvets dyed deep as ink. Their steps stop short as they fold stiffly into their pillowed seats, the settling of weighted cloth and the faint glint of rings as hands fold into laps. Whispers pass between bent heads.

At the pale-grey marble lectern centered on the dais, a red-robed Priore mounts the step, running his fingers across the stone, its deep grey veins crisscrossing through pale marble like the lines on a map. He lifts an arm in a sweeping arc, his sleeve unfurling in a gesture that takes in the seven contestants, the thirty-four seated judges behind him, the seven darkly gleaming panels, and before him, the packed audience pressed shoulder to shoulder beneath the octagonal vault.

Speaking with the authority of the Wool Guild, custodians of the Baptistery, his brassy baritone voice rolls through the hall, rebounding against the walls. The chamber breaks into a smattering of applause, before settling into coughs and the restless shifting of feet. And at once the proceedings begin.

The first goldsmith crosses the floor to stand beside the speaker as his name is spoken in full. He watches with wary eye as his panel is removed from the wall by assistants who carry it forward, straining, setting it heavily upon the lectern for the audience to view:

It is Abraham, burdened with the weight of his duty, his robes whipping in an unseen wind, and Isaac, but a child kneeling before the edge of a guilded knife. His mouth is open, but no sound comes. And above them, a brilliance — a hand reaching out.

The speaker’s words flow over the image — a sermon of sorts, as many in the audience lean forward, murmuring as if they might see. Yet few in the hall, only those close enough and keen of eye, see any more than a few glinting details. The goldsmith, wearing his half-smile as a mask, braces himself against the words, whether they be favourable or no. His eyes wandering the room, before bowing to the speaker, and returning, relieved, to his seat.

Another guilded Abraham is lifted from the wall. In this one, the scene lies shallow, barely pressed into the bronze, the figures timidly outlined, as if the craftsman had been afraid to claim the space. The speaker nods kindly toward young Lucco, earnest and pale, who bows his head as if in apology for the gentleness of his hand.

And still the procession continues, one frieze set down and lifting the next.

Outside, the sun wheels high above, tracing its slow arc across the sky. It lights first upon one facet of the baptistery, the light slipping off the slanted marble, and spilling upon the next — as if the building were nothing but a small octagonal sundial, drinking in the light to measure out the hours of this drawn-out theatre.

Inside, the judges nod, quills scratching at parchment, as if their verdict were yet to be decided. But Matteo, for one, knows this is all for show. The judges stare into the plain bronze backs of the panels as each has its moment upon the lectern. The decision would have been made weeks ago, in the Guild halls, where they could argue bitterly between themselves, no doubt. Or else why the delay?

From the benches, half-listening to the Priore’s droning praise, Matteo’s eye wanders, over the men seated in his row. Across the hall, sits young Donato among Lorenzo’s many apprentices — a fine face, though poorly dressed, his father only a wool comber. Yet he tips his chin high, a smirk tugging at his lips. Some are set to benefit no matter the outcome.

Across the hall, Donato grins. He knows each goldsmith well, and each of the seven panels bears the unmistakable hand of its maker. He laughs again, in delight. An artist, he thinks, is one who imprints his own true nature into the bronze, whether he intends it or not.

Lorenzo Ghiberti is called upon next. He strides across the hall, his robes brushing past the lectern on his way to stand beside the speaker and bows with grace, extending an arm wide to take in the judges. His Abraham brims with theatre, robes sweeping like banners across the frame, with gestures so broad they seem made for the stage. Lorenzo clasps his hands as if in prayer, the pink in his cheeks visible even to the women crowded in the back of the hall, the light seeming to favour him.

The audience sees a guilded scene gleaming, whole and convincing. But from the back, which only the judges can see, Lorenzo’s panel leaves a gaping hollow — as if a great chunk of bronze had been scooped out — seven kilograms of bronze had been saved in the pouring. In a door of twenty-eight panels, their cost would be greatly reduced, and all the judges know it. None more so than the banker among them.

Filippo shifts in his seat, twisting at the girdle that bites into his ribs. His shoes pinch, the stiff leather tightening, his feet swelling in the stifling heat. The lace at his throat clings, damp against his skin. One by one the names had been called, and all the others had crossed the floor and returned. Now he alone, hot and restless and full of agitation, remains to be called upon.

At last the words ring out:

“We call upon Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi.”

Filippo, who was son of Brunellesco, son of Lipo Lapi. He rises quickly, grateful to be moving. And although his feet ache more with standing, he marches heavily across the hall, arms awkward at his sides. Filippo stands before the audience, coarse-featured and plain, a heavy brow, a blunt nose — in garments fine but ill-fitted to his frame. And yet there is an unmistakable directness in him, a sharp intelligence that will not suffer fools.

His frieze is much the same: unsparing and dramatic in its tension. Where others had added flourish, he had held to the truth of the texts, rendering it with the sternness that the scripture had suggested — a father raising a dagger to a son.

He had thought it a strange image to present before a baptistery. The guild’s choice of story revealed much of their intent. Yet he had rendered it faithfully, perfectly, and without excessive ornament, down to the finest detail. The ones in the audience who can truly see, reveal themselves now, for they lean in nearer, as if something in the bronze had unsettled them. It carries a gravity that the others had lacked.

The speaker goes on, and Filippo grimaces despite himself as if the Priore’s words pain him, the words of praise ringing hollow to his ear. Does the bronze not speak clearly enough? Does it not speak for itself? With one sharp dip of his head to the speaker and one to the crowd, he turns and strides back to his seat — eyes fixed ahead, avoiding the silent laughter glittering in Lorenzo’s eyes.

On the dais, the quills are moving, scratching over parchment with the dry rasp of reeds, while judges cast sidelong glances at one another. The slips are gathered, counted, and stacked into two neat piles. The Priore turns, gesturing for the other — his crimson-robed counterpart, to join him at the lectern. The first Priore clears his throat as he lifts a slip of yellowed paper between finger and thumb. His voice rings out like a tolling bell.

’By my count, I have seventeen votes for Filippo Brunelleschi.’

The second Priore speaks, a honeyed tenor. His hands betray him, twisting in his coat-sleeves while delivering the words: ’I have seventeen votes for Lorenzo Ghiberti.’

High above the lectern, in the golden vault, a mosaic figure peers down spreading his arms out wide on judgement day. His gesture is one of calculation, subtracting a sinner’s deeds against his virtue — but today his arms remain perfectly level, unwilling to tip to one side or the other, as the numbers below come up even. Even the angels around him stop their wheeling, trumpets falling limp at their sides, to watch.

Below, the audience stirs, an astonished murmur fluttering through the crowd.

“As you can see,” says the first, tilting his head in consolation “the choice was simply impossible,”

“And so” continues the second, “It is proposed that the commission be shared between the two finalists.”

From the back of the hall a fan snaps shut and an infant’s thin wail cracks through the murmur, a mother’s voice hushing to soothe the swaddled babe.

“Impossible“ Filippo’s father scoffs, his words low, his head turning to left and right, seeking allies.

The two Priori of the Signoria raise their hands for quiet. “The two winners should work together,” concludes the first Priore, nodding in confirmation that the matter was now decided, and he gathers the two piles, stacking them as one. He eyes the audience levelly as he squares the edges neatly against the lectern. The second Priore lifts his arms in invitation to the two young rivals, with enough levity to lighten the room. The audience gives in to compromise and the chamber breaks into applause.

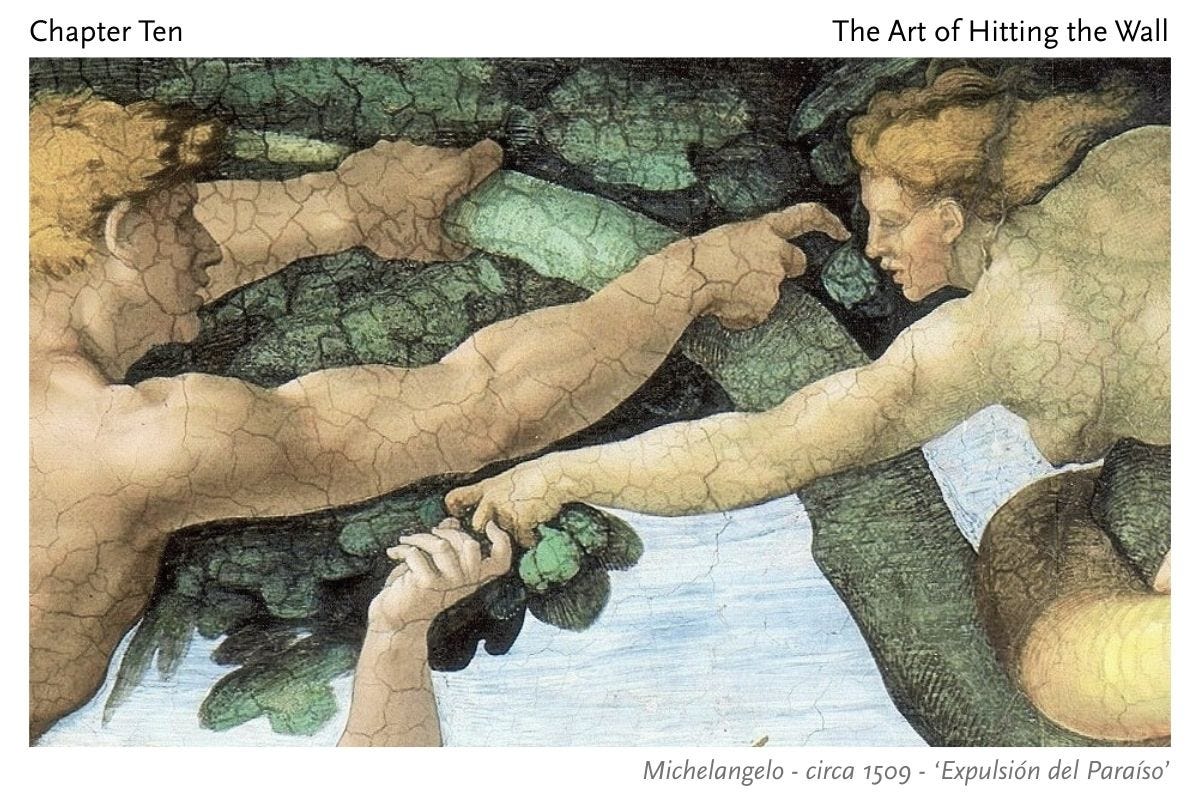

And Lorenzo, without wasting a moment — leaps up to cross the floor, drawing the crowd’s eye with him. Behind him Filippo follows in his wake, uncertainty dragging at his heels. Lorenzo mounts the marble step, bowing with a flourish that sweeps the hall, and turns, so graceful that it feels rehearsed. Facing Filippo, he extends a hand — a gesture of welcome, a hand poised to draw Filippo up into the space beside him. Yet in that very gesture, he towers above, claiming the height, leaving Filippo reduced by the very invitation.

Three golden rings glint, set on the fingers of Lorenzo’s outstretched hand — a palm as soft as a newborn babe.

And Filippo sees it.

There are moments where time folds in upon itself. A single gesture throws open a door, and the years spread out before you — the child, the apprentice, the master, the man — strung together like stars across a darkened sky.

Filippo, looked upon that soft unmarked hand. It was so unlike his own. And there he saw an image — of himself as a man bent low in another’s workshop, streaked with soot and ash. Around him, apprentices hammering in time, but never to his command. Above them, Lorenzo would parade like a prince, basking in praise, taking the credit and coin. Lorenzo, who would gladly melt a panel down and recast it whole if the purse jingled with enough gold.

Before long Filippo would be told where to set his tools. Soon, he too would be taking instruction from the baker’s boy.

Filippo saw all this, written in that one smooth hand — a row of golden rings glittering before him like tiny suns.

A sharp intake of startled breath tears through the chamber, a single inhalation by a hundred open mouths. Without realising it, Filippo had already taken a great step back.

He had not meant it. It was as though the ground itself had shifted beneath his feet. He needed nothing more than a moment’s pause, a sliver of time to think — yet his body had betrayed him, his heel sliding out behind to steady himself, as if the hand stretched before him was not an invitation but a serpent poised to strike.

They had all seen it. And it could not be undone.

The silence that follows is unbearable, ringing louder than a bell. He watches Lorenzo’s face and sees the half-smile still painted on his lips, but hardened now, eyes sharp — glinting daggers.

The gasp still hangs in the air as Filippo turns away. The judges sit frozen on their dais, but he only walks on. His heels strike marble, the echoes too loud, ringing unnatural in his ears, so that he quickens his pace, cloak dragging at his shoulders. Whispers collect in his wake and heads turn silently to follow him, tracking his progress in disbelief. Somewhere in the benches his father flushes, as the colour rushes to his face.

But Filippo is almost to the doors now. Eyes stinging, he fixes his gaze straight ahead, avoiding the gleaming sliver of cream brocade appearing just at the edge of sight. He knows the pomegranate pattern is there, and with it his mother — her pale egg-white skin cracking into fine lines as her face stretches into a mask of worry.

The doors loom before him, three times his height, and twice as heavy. He lays his hands against them, cold against his fury and they gape open, sending a sharp wedge of sunlight to slice through the hall. The audience, already craning their necks now lift hands and elbows to shield their eyes against the sudden blaze.

Then the doors shut behind him.

Daylight blinds him, dazzling white, broken only by the thin chirp of birds twittering in the empty piazza. And scattered chinks of sunlight pushing through the parting clouds. The air is icy against his flushed skin. He pulls off his cap, releasing a wave of sudden coolness as he passes his fingers through sweat-dampened hair. Giddy on the cobblestones — he feels crazed, and lost, and free.

He turns in a half-circle, swinging back to stand before the Baptistery’s dark door, sealed now, he feels that it might never open again. He will not be there when it does. With sudden urgency he moves away, marching briskly across the square and down the quiet street, as if sensing the townsfolk chasing at his heels. And all the time thinking: What have I done?

As he crosses street after empty street, the cathedral’s broken drum peeks out at him from over rooftops, as if regarding him for the first time.

Image Credit: Michelangelo - circa 1509 - ‘Expulsion del Paraiso’

“Cabbage” I can relate to that reaction/decision. Lovely Tara.💕