Chapter 7: The Edge of a Guilded Knife [Part I]

Not far from the cathedral, in the wealthy quarter where the bankers and silk merchants live, a single room still flickers with light. The candles are burning low, dripping shallow pools of wax into the brass bellies of a pair of candlestick holders. A soft amber glow spills out across a writing desk strewn with parchment.

Thick velvet tapestries hang on the walls, richly embroidered with pomegranates and vine leaves, their curling edges picked out in gold thread.

Pacing in front of the writing desk is a young man of twenty-four. His features are plain, hardened by labour, and tipped with a fury too restless for sitting.

He does not seem to belong in such a room as this. He looks misplaced among its fine finishings, though this is the room of his childhood. His hands are rough and calloused, bearing stains that have seeped so far into the skin that it would be impossible to wash them out.

His boots tell a similar story, worn thin, and dusted with soot and ash, scuffing the terracotta floor tiles with every turn — agitated, as Filippo replays the same moment again and again.

He paces.

The judges. The verdict. The outstretched hand.

That look of smugness on Lorenzo’s face.

He cannot let it go.

Just beyond the cathedral steps stands the Baptistery of San Giovanni, an octagonal stone building older than the cathedral herself, clad in the same striped patterning of green and white marble.

Like every child born in Florence, Filippo had been carried through the Baptistery’s ancient doors on the Sunday after his birth, swaddled and wailing in protest, baptised in water drawn from the Arno, and given his name.

Now he was a man, grown. Trained as a goldsmith and a clockmaker.

In the heat of the previous summer, 1401, the silk merchants had announced a grand commission. A new set of doors for the north side of the Baptistery. And they were to be adorned with twenty-eight gleaming panels, all depicting scenes from scripture, cast in bronze and guilded with shining gold.

To a goldsmith, it was everything, a commission that would define a career, and for Filippo, it had arrived at precisely the right moment. He was no longer just a promising apprentice, he was gaining recognition for his skill. Imagine it, every merchant, artist, every barefoot babe and dignitary, pausing beneath those doors, their eyes resting on stories told through his hand. Hands that might be remembered for decades.

Centuries, perhaps.

There had been a competition.

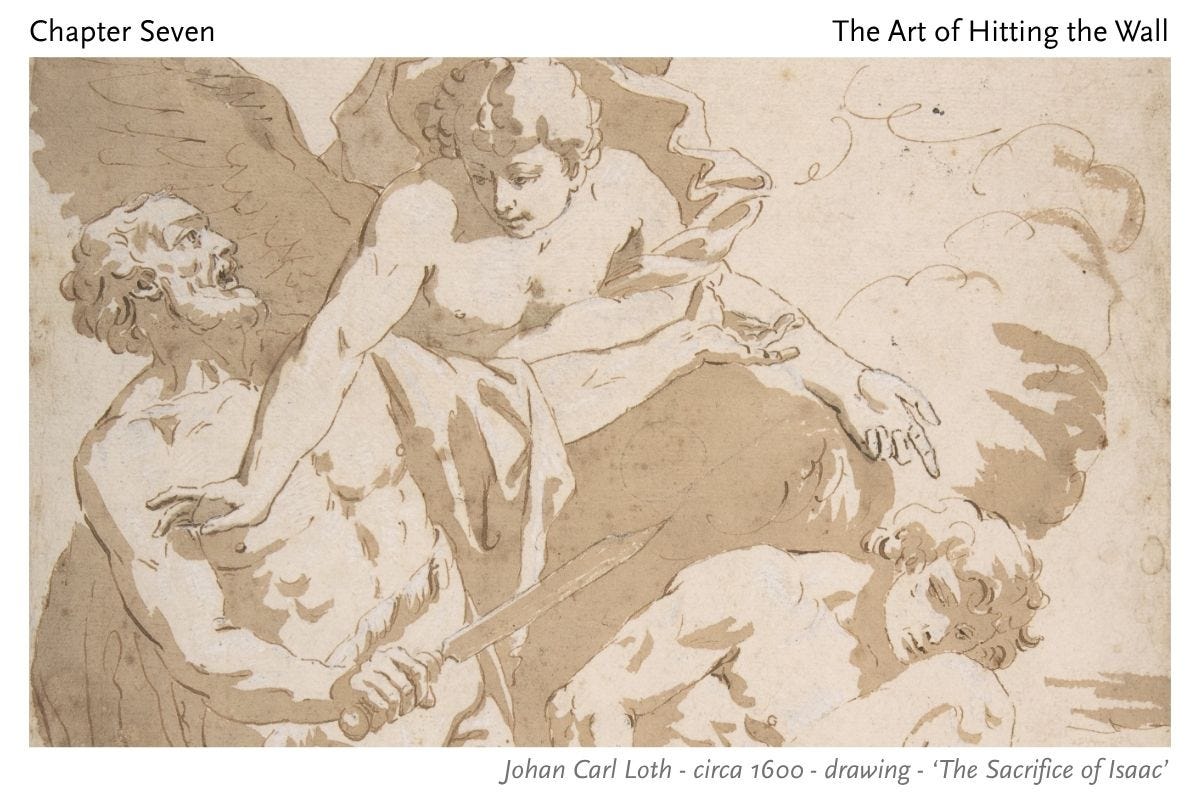

Seven artists stepped forward with Filippo among their number, each one trained as a goldsmith under Florence’s Arte della Seta guild. Each charged with the same task: to depict a scene from the Old Testament — the Sacrifice of Isaac — in guilded bronze.

The winner would be awarded the entire project, all twenty-eight panels. The commission of a lifetime.

At twenty-three, brimming with talent and skill and restless purpose, Filippo had thrown himself into the work.

It would take over a year to design and render the scene.

Before Filippo would pick up his charcoal to make the first sketch, he read the story again and again, studying the Latin texts in their fine calligraphy until the feelings lodged in him like a stone and he ached with the grief of it.

The scene haunts him still.

The boy, Isaac, discovers too late what his father intends. He opens his mouth to protest, but it comes out in a garbled wail. Abraham’s arms ripple with the strain, his robes whipping in the wind atop the rocky Mount Moriah. The knife glints in his hand, his grip, iron, his expression, unreadable — his eyes are fixed on his son, but seeming to look through him, to something else, out of the reach of reason.

The boy with gritted teeth, cowers, shielding himself against the blow, his eyes shut tight and streaming.

No, that's not it. We need to see his face.

The father's hand wraps around Isaac’s pale throat, the boy’s knees buckling on the altar built for sacrificing sheep, already bloodied, the knife already touching skin.

Isaac strains to look up, away from the blade, and sees above him, uncomprehending, his father’s eyes, crazed and wild, now locked on something else.

Something brilliant, feathered, a hand reaching out to stay the hand that slays.

But Abraham’s left arm would hide the knife’s edge from our view. Does the angel reach him in time to spare the dutiful son who tended to the sheep and carried water, asking no questions, obeying his father?

The bronze will never say.

Filippo will leave the scene suspended in bronze, a question to be answered only by one who has heard the story and knows the ending.

That's the way.

Gently, Filippo reaches for a stick of charcoal. Carefully, as if not to disturb the image in his mind’s eye, holding the scene lightly as if gripping it too tightly will make the angel, Michael to turn his head, missing his chance to save the boy.

Image Credit:

Johan Carl Loth - , circa 1600, drawing, ‘The Sacrifice of Isaac’, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Subscribe to ‘The Art of Hitting the Wall’ so you never miss a chapter.