Chapter 7: The Edge of a Guilded Knife [Part II]

Through a narrow sliver between the workshop’s double doors, the street passes by in fragments. A swish of skirts, a basket swinging from the crook of an elbow, little boys shrieking as they chase pigeons, a pair of builders balancing a length of timber between them, calling out warnings to the crowd ahead. Apprentices dashing between workshops. Each, just a glimpse, and then gone again.

Filippo does not look up.

Up and down the street in the goldsmiths’ quarter the workshops have their doors thrown wide. It is the custom in Florence — an invitation to trade, but also, a signal to the guild. An open door means we keep no secrets, no slipping a little bit of gold into the pocket, or swapping a sapphire out for tinted glass. Passersby drift in and out, making conversation, watching artisans at work.

But farther up the street, where it begins to narrow, Filippo has drawn his doors to only a crack, enough to observe the guild’s law — but not an inch more.

The street outside is too bright, too loud, too garish, his clay scene too soft and malleable. He is shielding it from the sharpness of the world. His workshop doors dampen the harsh sunshine, the shrill burst of laughter, the barked command, the clink of hammers on tempered steel from a workshop nearby.

Inside, the air is cool and thick with the scent of damp clay, the furnace cold. Light spills through the crisscross of the iron grill above the door, casting a patterned square that inches across the terracotta tiles with the afternoon sun.

A fly buzzes past his ear. He swats it away, without looking up.

Filippo leans in, his whole body curved forward, a patch of sweat blooming on his tunic between two broad shoulder blades.

He is here, hunched in his workshop, carving every detail into the soft clay — the woolly fleece of the ram, the fine feathers on the angel’s wing. In moments, he can almost see the small chest of Isaac, rising and falling in short, shallow gasps.

A steady clip of boots on cobblestone abruptly stops. A knock. Four neat taps against the door, and then it creaks open. Filippo raises his hand to shield his eyes from the sudden brightness, squinting. He cannot make out the features of the person in the doorway — a man, he thinks — shot through with beams of light among rising dust particles catching the sun. The visitor pauses for a moment longer, taking in the rough-looking Filippo, unshaven and dishevelled, then with mumbled apology, they push the doors back to where they had been before, revealing the same sliver of the now-empty street.

Filippo finally shifts, his movements slow and stiff, stretching and looking about the room.

On his workbench, the parchments pile high with charcoal studies, a paper trail from weeks spent chasing the composition, each revision pulled tighter, to fit within the constraints of the gothic cloverleaf base — the quatrefoil. It’s a difficult shape to work with. He had coaxed the story within its frame, like a shepherd guiding sheep.

In the corner of the table: a plate of olives, a hunk of bread, a thin slice of cured meat, all congealing in a puddle of grease. The crust has gone hard. Two flies drone in lazy circles as a goblet of wine sits, untouched.

Filippo turns back to the scene in clay. A fold of Abraham’s flowing robes catches his eye — it hasn't caught the wind just yet. He leans in again.

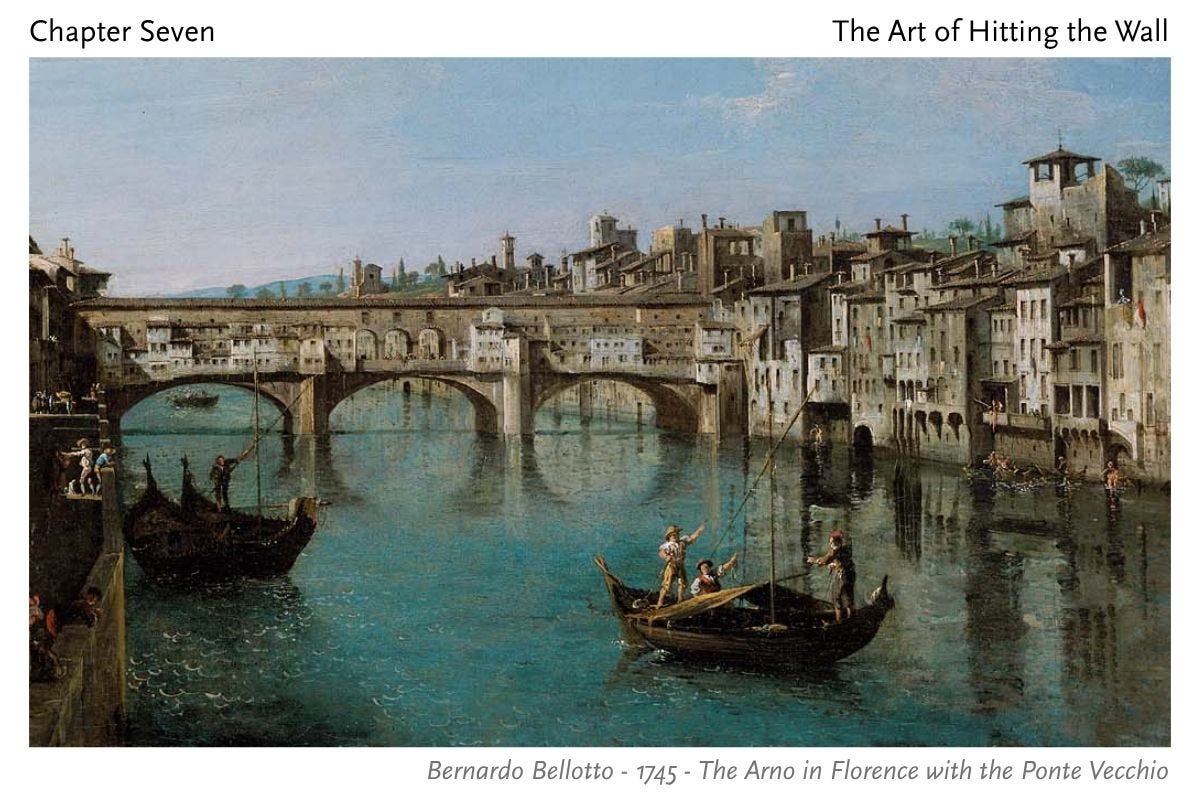

The Arno glints, rippling in the morning light, as pale sparse clouds stretch wide across the sky, their edges touched with pink. On the far bank, a flat-bottomed barge is ferrying a heap of fleeces, another is unloading barrels of olive oil. The boatmen steer with long poles, calling to one another, their voices echoing strangely over the water.

Filippo walks beside his younger brother, Matteo, in the quiet of morning. He notices Matteo walks a little taller these days. Since taking up his post as an apprentice to a civic official, his voice has taken on a crisp, assured tone — one that Filippo hadn’t noticed before.

Matteo speaks of committee meetings, held in vaulted rooms, with frescoed ceilings and marbled floors, where men debate trade routes and guild regulations. He talks of agendas and policy and civic duty. He has developed a fondness for procedure now.

Filippo listens, but his thoughts are elsewhere. In such rooms, he imagines, he would spend more time studying the ceilings than any debates taking place beneath them.

Matteo had taken the path that their father had dreamed for his sons, of law and rhetoric and public service. And Filippo is glad, truly glad, that it suits Matteo so well.

It would never have suited him.

They arrive at the steps of the Palazzo, where Matteo is due to attend a public address. At the top, a small group of gentlemen gather, their robes, heavy with status and fingers bright with golden rings.

Filippo steps back, studying Matteo from the base of the stairs. He watches the way he smooths his sleeves of his coat. He sees the invisible pull as Matteo is drawn toward the conversation above, a subtle nod of recognition. He places one boot on the first step, then turns back to face him.

A nod is exchanged between brothers, a silence full of things left unsaid. Then Matteo turns, climbing the stone stairs. Filippo lingers a moment longer, lifting his gaze to see how Matteo is framed by the carved stone arches above the doorway. A figure already halfway into the world above.

Filippo turns.

The sun has cleared the rooftops now as he makes his way to the goldsmith’s quarter. The sounds of industry gather, hooves striking cobblestones, the glorious ring of hammer on metal.

A world that makes sense to his hands.

Back in his workshop, the clay has hardened. It is ready.

He rolls up his sleeves, hands twitching with anticipation.

There is work to be done.

Filippo arranges a handful of charcoal in the smaller furnace. He doesn’t need much heat. It catches slowly, releasing a faint, bitter scent of carbon as the coals begin to glow.

Then he places a small lump of golden beeswax into a metal pot, watching as it softens, then melts, turning liquid as a warm, honeyed, scent rises.

When it swirls clear, he dips his brush and returns to the scene in clay. Carefully, delicately, he paints the surface, coating each rise and hollow, sealing every detail beneath a hardening skin of pale ochre wax.

There will be no more revisions now. The scene is sealed in wax. Filippo walks to the workshop doors and throws them open wide, letting the sunlight, the noise, and the life of the street spill in.

Image Credit:

’The Ponte Vecchio, Florence,’ 1745, Oil on canvas by Bernardo Bellotto. From the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Dear readers,

These historical chapters are a little heavier in the research than I expected, so I’m not quite moving at the pace I had hoped. Chapter Seven: The Edge of a Guilded Knife will continue over a few more installments to come. The next installment, ‘Chapter Seven: The Edge of a Guilded Knife III’ is coming next week.

‘He had coaxed the story within its frame, like a shepherd guiding sheep ‘ ❤️ lovely 🌷

….he had coaxed