Chapter 7: The Edge of a Guilded Knife [Part IV]

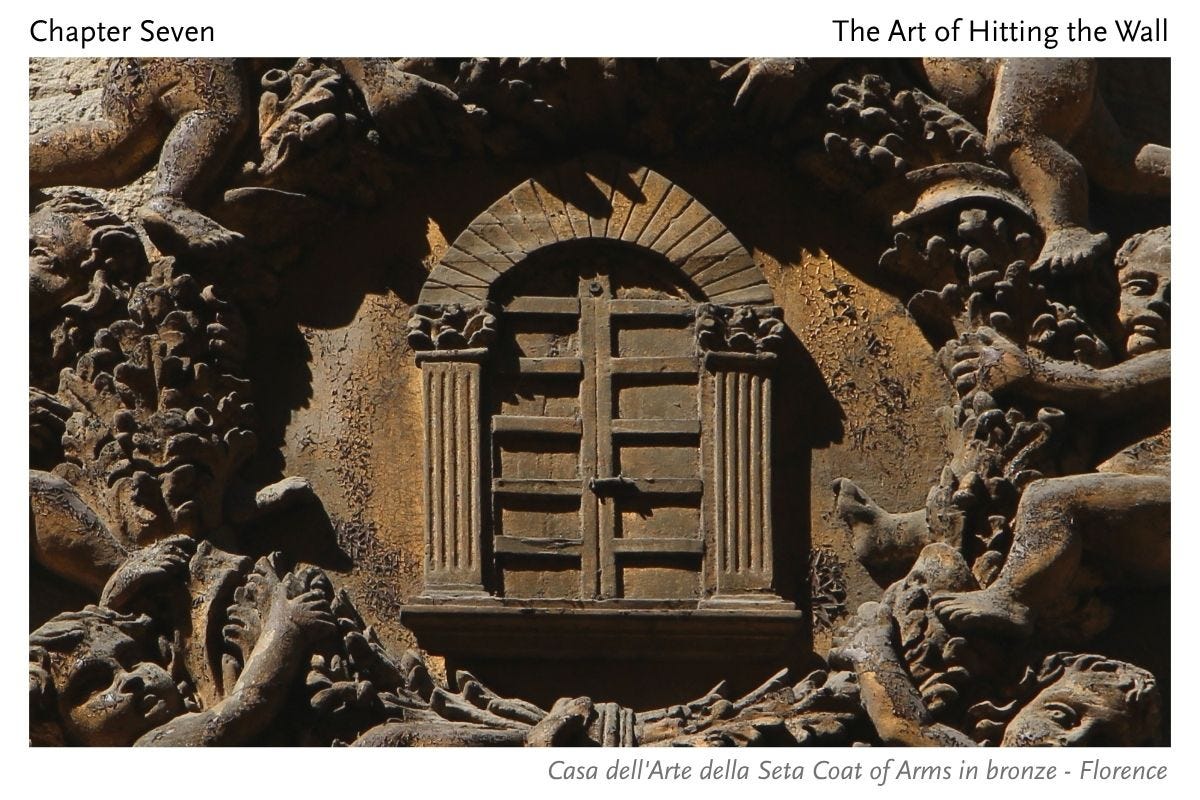

The double doors of the Arte della Seta Guild stand solid and imposing, dark wood bound with bands of iron, framed with thick stone columns rising into a great stone arch. They serve as a reminder to all who pass by that the Guild of Silk and Goldsmiths is a door not open to all. To enter, you must earn the right.

Beyond, the corridor stretches awhile before opening into a large echoing hall. Two guild officials stand beside a heavy iron scale, its chains creaking softly with the weight of copper ingots — warm, rosy, and reddish-gold in the lanternlight. Each ringing a dull chime as one is stacked atop another.

A heavyset merchant lifts each bar in both hands, placing them neatly in a growing pile. He moves with ritual precision in a coat of crimson, lined with saffron silk. A matching rounded cap sits snug atop his head, nearly covering the grey at his temples. He nods once to Filippo, his eyes glistening softly, as a money pouch sways at his waist, suspended from a fine leather belt.

The second merchant, tall and wiry, calls out the weights from the scale, enunciating more clearly than strictly necessary. His voice is clipped, sharp, echoing in the high-ceilinged hall. He wears striped stockings in indigo and slate, a hint of lace at his collar and cuffs. He watches with piercing eyes as a porter steps forward and begins to carefully wrap each ingot in linen.

Filippo lifts one of the copper bars, testing the weight of it. The surface is faintly murky, brushed and striated with fine imperfections. It is tapered, stamped with the maker’s mark, and cool to the touch.

Beside the counter, two handcarts wait, each packed with straw to muffle the ring of metal on metal. Better not to draw too much attention. The porter begins stacking the wrapped copper bars into the carts.

The tin ingots are smaller, silver-grey, and slightly mottled, a lighter clink as they’re added to the carts — nine parts copper to one part tin. The ancient recipe, passed down from the Romans.

And a little something else, too.

The merchant produces a flat, dark, dense piece of lead, no larger than a deck of cards, and places it in Filippo’s palm. It is heavier than it looks.

In the furnace, lead stings the nostrils and gives off a sour metallic taste in the back of the throat. Metal fume fever brings headaches and stomach pains — or worse. But it aids in the pour, making the bronze alloy more fluid, letting it reach all the fine details for a better finish.

Such is the cost, Filippo thinks. Beauty always requires a little poison.

He glances at his father, searching for a subtle sign that all is in order, knowing that his father gives little away.

With a nod from the merchant, The porters throw on more linen coverings and fall into step behind them. The wheels creak under the weight of the load.

Filippo and his father turn and make their way down the long corridor, their steps echoing behind them. As they reach the threshold, the man in the striped stockings leans to the other, stooping slightly.

"A curious detail," he whispers, “that Master Ghiberti’s order had come in light — a few kilograms short, by my count.”

The other shrugs and furrows his brow, looking back at the two figures, small now after stepping out into the street — shrinking into the light, the large doors swinging closed behind them.

Outside, the wind is rising.

It whips through the narrow streets, catching folds of fabric, tugging at cloaks and sleeves. It whistles between buildings and down alleys, up into shutters and pulling them loose. The porters hunch forward as they push the handcarts beside father and son, silent behind creaking wheels. Straw muffles the sound of metal, but Filippo hears it still — the slow, steady march of his copper and tin.

The sound of it shakes loose his hands’ memory, taking him deep inside the process. Though his feet are striking stone beside his father, his mind is already lifting the crucible, steadying the pour. Though the bars beside him are solid, wrapped in cloth to quiet the sound, in his mind they’re already white-hot — flowing into the hollows he’s carved, chasing every edge. He prays the lead will be enough to thin the alloy, to help it slip like water into every detail.

He must choose the right day. Not too hot, not too cold. A still, dry morning with not a breath of wind. When the conditions align just so, that will be the day when the alloy will take its shape.

He doesn’t look at his father, but he feels the silence stretching between them, growing louder with every step.

He knows his father sees the panel as a move in a larger game — one piece nudging another across the great marble chessboard of Florence. The competition, the guilds, the halls, the judges. It’s all a game to him, he sniffs.

Filippo had once tried to play that game. He had the beginnings of an education in law. But he had found the words to be slippery, truth too easily bent to suit the atmosphere of the room.

Filippo’s hands wanted something solid. His work would speak for itself.

In the distance, a bell strikes two. The sound ringing across the water. The air is sweet with the smell of roasting chestnuts, before the wind whips it away again.

The carts hit a rut and jolt, a low clang rings out, and Filippo flinches, but his father says nothing.

He tries to stay in the ritual — imagining the furnace and the pouring, but his mind drifts, as it always does, to Ghiberti.

The foolish Lorenzo, he thinks, shaking his head. He opens his process to anyone with eyes to see. His studio is a fishbowl, with students, merchants, apprentices all drifting through. Nobody passes Ghiberti’s door without being pulled into some question. “Do you think the angel’s wing should come forward or be tucked behind? Should the hem of this robe follow the wind, or lie still?” Even the baker’s boy weighed in.

A master, Filippo thinks, is one who trusts his own instincts.

A design by committee is no design at all.

The judges will see right through Lorenzo, he thinks, If the judges aren’t fools.

They round a corner and the wind hits them full in the face. Filippo lifts a hand to shield his eyes. Across the Arno, the towers rise pale against a sky that’s beginning to grey. A storm is coming.

He watches his father’s face — stern, composed. A lifetime of restraint etched into every line. He does his thinking behind a face that doesn’t give anything away, never revealing his hand until every variable has been weighed. Twice.

Filippo remembers the early skepticism — the raised brow, when he’d first turned away from the path of law. But over time, as Filippo’s hands learned to shape what others could only imagine, his father’s stance began to ease. A quiet pride in small gestures, never spoken.

His father walks with his hands clasped behind his back. His eyes scan the floor out of habit, noting where the cobblestones have begun to crack.

Filippo doesn’t see the way his father watches him.

Brunellesco looks at his son beside him — taller now, darker around the eyes than he used to be, his clothes worn thin by labour.

He wonders what it must be like — to form an idea and to believe in it so completely that you are willing to pour molten metal into that shape, to let it harden and cool into something final — without ever knowing the future.

He cannot imagine it.

To him, truth is earned through negotiation. It shifts with time, and circumstance, with alliances, and changing winds. It must be tested, weighed, and adjusted. That is the art of the game.

That Antonio and Filippo are two sides of the same coin is plain enough to see. He chuckles softly, imagining how they would both rail against the comparison, but there’s no mistaking it. He shakes his head, his eye catching on one of the handcart’s wheels, in want of repair. Filippo, in pursuit of his perfect forms and radiant truths looks to him just like Antonio, chasing his monks through the holy city, trying to touch the divine.

Both running after absolutes, like boys running after pigeons.

But Brunellesco has seen what youth cannot yet imagine.

He remembers the plague — how quickly he saw ideals turned to ash. The same men who once debated the soul turned to hoarding grain and bribing guards — the finest minds yielding to necessity.

Let the boy live through a plague or two, he thinks, not unkindly, as they near the workshop doors. Then, perhaps, he might see reason.

On a windless morning in April, a man stands outside Filippo’s workshop, forearms slick with sweat, his tunic clinging to his back. Gasping, he cranes his neck skyward, desperately willing a breeze that does not come. His mouth is chalk-dry, face streaked with soot.

The street bustles, but passersby give the workshop a wide berth, as the air around it shimmers with heat, and foul-smelling fumes. With one more deep breath, he pulls the damp cloth back across his face — and steps inside again to join the others.

The crucible glows incandescent. The furnace roars. Inside, the brightness splits the scene into the harsh contrast of white and black.

As the temperature reaches its highest point, iron tongs reach to grip the crucible, slow, steady — tipping.

They brace their legs as the molten metal pours white into the mould — hissing, sending up a wave of heat and smoke. Bronze flares out of the narrow vents, a sign for the men to stop.

With a thud, they lower the crucible and step back.

One by one, the men stagger outside, gasping for sips of air. Others remain, shovelling sand, packing it in layer by layer to slow the cooling — to temper it so it does not crack.

Filippo tastes metal — dry, blood and copper coins. His muscles tremble from the strain, but still he holds steady until the last corner is buried beneath the sand.

Heat still radiates from it, a shimmer rising from beneath the sand, a mirage distorting the air.

Then it’s done.

The men wipe their faces. Coins change hands. They nod, wordless, and leave — desperate to escape the heat.

Hours pass and the furnace, still glowing, begins to dim as it hungers for charcoal spent. From white, it begins to burn yellow, then orange, then with flecked with red.

Long after dinner, Filippo returns. He cannot sleep. In the workshop, the heat clings to the walls. There is nothing here to do, but wait till the bronze is cold. Only then will he know.

Instead, he stands in silence, listening to the tick tick ping — the sound of metal cooling — shifting, uncomfortable in the prickly heat.

At last, he steps outside, the cool night air touching his skin, and lifts his eyes.

Above the workshop, the heat rises in waves, rippling the stars — like silver coins tossed up into the dark wishing pool of the sky.

Evening gathers in the streets and the last of the bells have stopped their ringing.

Livia steps out through the side door of the chapel, pulling her shawl close. The scent of wax and soup clings to her. The night is clear, the stars sharp as arrows against the darkened sky.

Under her arm she carries a stack of empty bowls and plates — the remains of a supper she'd brought earlier for Caterina and Maddalena, who’s mother was sick with fever. She had trimmed the candles for the evening service, checking the wicks.

More than a hundred candles burned, flickering in the chapel, the air thick with prayers and smoke. Her lips moved slightly as she lit one for Beatrice, who had just lost a son. For her husband — may the scales tilt in his favour this time. One for Matteo, who stays late copying ledgers, hoping Signore Bardi will recognise his talent.

And one for Filippo. A pause.

For Donato, and Lupo, and Nato, and Berto — every boy who had helped with the pour.

She didn’t linger.

When she reaches the house, she slips off her shoes at the threshold, and moves quietly through the entryway, setting down the dishes. Bare feet tiptoe past embroidered tapestries and up the weathered steps. The lamps have already been dimmed. No one sees her return.

Her feet are red at the seams where her shoes had been digging all day. In her chamber, she presses her thumbs to release the ache in her arches. Alone, she unpins her hair — the weight of it falling forward as she lowers her head.

She kneels beside the bed, her hands clasped,

This is not a prayer she would speak aloud.

“Sant'Eligio,” she whispers. “Patron saint of goldsmiths, of honest hands and hammer-sparks.”

In her mind, she steps not into the church, but before the Baptistery of San Giovanni — the same space where, on the eighth day, she brought her newborn son, wailing so loudly she thought the marble itself would crack. She chuckles softly in the darkness, thinking that she had never heard a child who screamed like Filippo in that place.

Now, in her mind, she is kneeling, not beside her bed, but with her knees on the cold stone of that sacred floor, and before her, rising, she sees them — all twenty-eight panels. Two columns of seven on each door, gleaming with a kind of internal light.

She throws them open — her arms lifting before her, and into that sacred space, she sends the full force of her plea.

Let the twenty-eight panels be enough.

Let them temper him.

Cool him.

Keep him.

Tether him.

She sees their golden scenes etched like glittering anchors — each one forged in the fire, each one holding a corner of his restless soul.

Twenty for the life of Christ, Four for the ones who told the story of the gospels, and four for the church fathers, who led their sheep. Not one of them could see those panels as clearly as she could — not like a mother.

Let the work be heavy.

Let it slow him.

Let it hold him to Florence.

Let it hold him to us.

Her son.

There is a gap, a hollowed place where hands have clawed and scraped. Beside it, Filippo steadies himself beside the mound of cooling sand. One knee in the dirt, he raises the hammer high above his head.

And he hesitates.

The mould is still warm, the last of its heat rising, fired bisque caked with sand.

The act of revealing is also an act of destruction. To reach the bronze inside, he must destroy the very form that shaped it.

There is no way around this.

The wax, the pouring, the months of preparation. The mould cannot be reused. If the bronze inside is cracked or misshapen, he would have to start again.

From the sketches.

For a moment, he is very still. Then he tightens his grip.

And with force, he brings the hammer down.

The blow lands with a cracking thud.

Hairline fractures spread across its surface. Dust and sand lifts into the air and settles slowly as a copper tang fills the air. Another strike, and another, until the shell begins to break apart. A glint of bronze catches the light and he sets the hammer down.

With bare hands, he pulls apart the crumbling clay, slowly — as if removing the bark to rescue something yet alive.

A fold of cloth. The curve of a wing, and then the boy’s face.

The bronze inside is rough. Dull.

Pocked with tiny bubbles and fine surface scars. Sharp raised edges and a line where the metal cooled too quickly.

Filippo lowers himself, until both knees press into the sand. He runs his calloused hands along every inch of the bronze. His fingertips trace every imperfection. Every pockmarked surface. Every sharp edge. Every flaw.

There is so much work ahead — it will need to be filed smooth, chased and refined. With agate stones and with fine chisels.

He breathes a sigh of relief, as a grin spreads across his face.

It is whole.

Image Credit:

Casa dell'Arte della Seta Coat of Arms in bronze - Florence

Tara, you are a time traveler 🧳 ❤️

Absolutely striking! So well done Tara!! It is like you have lived there 😱😱😱