Chapter 7: The Edge of a Guilded Knife [Part III]

The River Arno splashes in ripples of olive green, like dirty paintwater, lapping merrily against the thick stone arches of the Ponte Vecchio. The street that crosses the water is crammed with shops and the bright sounds of commerce. It is mid-morning, and the bridge heaves with foot traffic — none moving more swiftly than a boy of fifteen, carrying news.

He is lean, with the lightly muscled frame of a sculptor, long brown curls framing a striking sun-bronzed face. He barrels down the street, boots skimming the stone, weaving through the crowd. Around him, the bridge is alive with colour and motion, farmers unloading baskets of figs, fishmongers with silver-scaled catch, and cloth sellers lifting bolts of dyed fabric into the light.

“Why do they move so slowly?” he thinks, frustrated — unaware that it is the swiftness of his own youth that makes the world seem so slow, as if the whole street were wading through honey.

He swerves past a man hefting a sack of flour, sidesteps a mother scolding her child, and nearly collides with an old woman leaning heavily on a walking stick.

“Mi scusi, signora!” he calls, steadying her with a hand on her elbow.

She waves him off with a scowl. He offers her a broad grin — his big brown eyes dancing — before slipping past two men rolling a wine barrel, the wine sloshing with every turn.

At last, the crowd begins to thin.

As he rounds a corner onto a quieter side street, his fingers brush against a block of pale weathered marble set into the wall — a break in the monotony of sandstone. It juts slightly outward, a detail easily missed in motion, cool and solid, steadying him as the sounds of the bridge fall away behind him. He does not notice the faint indentation beneath his thumb where a Latin inscription had once been carved, rubbed smooth by centuries of sand and weather.

He slows only when he reaches the double doors of Filippo’s workshop, and without so much as a knock, he dashes inside.

Inside, the heat wraps around Donato like a blanket.

The air is a thick haze, the sharp smell of burning charcoal rising around the furnace. Filippo, sleeves rolled up to the elbows and flushed from the heat, is working the bellows in a steady rhythm, drawing them wide, pressing them together, fanning the flames higher.

“Pippo!” Donato grins, stepping closer. “Did you hear —?”

But Filippo doesn’t hear him over the roar of the furnace. He is darting towards the open mouth, checking the airflow, his whole body attuned to the flame.

Donato stands back for a moment, taking in the scene — the shimmer of heat, the master at work, and the warm earthy-smell of burnt clay and beeswax. He knows this world well. His own hands are marked with burns and callouses, apprenticed as he is in a workshop farther down the street — the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti.

Donato moves toward the bellows to help.

“Stop,” Filippo calls, laughing as he catches sight of him. “I’ve got it. But thanks, Donato,” he says, slapping his friend on the back. “I thought Ghiberti had you working so hard I wouldn’t see you.”

Donato shrugs, grinning. “I escaped.”

Pointing into the furnace, Donato asks, with some reverence. “Is that it? Your Sacrifice of Isaac?”

Filippo nods, wiping his brow with the back of his wrist. The flames are licking around a hulking mass of clay, a hard shell formed around the wax scene inside.

“I wish I could see it.”

“You’re about to.” Filippo gestures, grinning toward the mould.

For a moment, a flicker of confusion, and then Donato understands the joke and grins.

They both watch as threads of pale amber beeswax begin to seep out, bubbling and then dripping out through small vents in the clay shell. The wax hisses and smokes where it meets the heat, dripping and pooling into a blackened metal pan below, the wax shimmering in the firelight.

“There,” Filippo says, nodding.

Donato scrunches up his nose in mock distaste. “Isaac looks a bit lumpy, don’t you think?”

Filippo beams, proudly, eyes never leaving the mould. “You’ll see when he’s in bronze.”

The two young men stare into the flames, light dancing across their faces. Filippo seeing his image, the sacrifice of Isaac dripping into the pan, and Donato imagining the scene as he knows it — the one that is taking shape in Ghiberti's studio.

The wax and clay enter the fire together. The clay must endure, but the wax will not.

Beneath the clay shell, the same heat that hardens the clay is melting the wax from within. It seeps out leaving behind a hollow that holds the memory in reverse of a scene from scripture, empty, waiting to be filled with molten bronze.

Filippo grabs two pairs of iron tongs — one in each hand — and moving quickly, he steps toward the furnace.

Donato watches closely, his brow furrowing. Without a word, he reaches for another set of tongs, from the wall, clasping them firmly.

Together, they grip the clay form, its surface scorched and weeping. They begin to turn it — slow, deliberate. Grunting with the effort.

“This is not a job for one person, Pippo,” Donato says through clenched teeth. “Why do you insist on doing everything yourself?”

Filippo doesn’t answer.

Donato exhales through his nose, adjusting his grip.

Donato had apprenticed under Ghiberti, in a workshop swarming with hands. Hands to stoke the furnace, to tend the bellows, to shape the clay, to turn the moulds.

Here, there are only two, the roughened hands of Filippo, who carries all the work himself — and whoever happens to be near enough, and stubborn enough, to insist on helping.

They rotate the heavy shell again and again, letting the last ribbons of beeswax drip free. Filippo peers into the vents, checking for smoke, for bubbles. Then, satisfied, he nods toward the drum of sand beside them.

With a practiced rhythm, they carry the mould over to the drum and lower it gently, burying it in the rough sand to temper the cooling.

Filippo exhales, deeply. He wipes his face with the front of his tunic, his hair damp with sweat.

Donato steps back, watching him for a moment — and then remembers.

“I came to tell you, Antonio’s back.”

Filippo’s eyes open wide with surprise, and then narrow with interest.

“He arrived late last night.”

Antonio, the brave fool who had left Florence to see Rome the previous spring — had returned.

Livia’s table is laden.

Tuscan bread, unsalted, sits beside a shallow bowl of glistening olive oil. Blackened onions roasted with vinegar and herbs, thin slices of salted cod, and piles of shaved pecorino, curling at the edges.

Steam rises from the heavy clay pot at the centre of the table, cabbage soup, thickened with white beans, and infused with garlic and rosemary.

She scans the faces around her table.

Her youngest son, Matteo, sits beside her on one side, her husband at the head of the table. Directly across from her, Filippo, her middle son, is flanked by his two companions: The young sculptor, Donato, who is no stranger to her dinner table, and the traveller, Antonio, recently returned after more than a year away.

There is warmth in the room, and the sounds of shared laughter — but what pleases her most is seeing Filippo, usually so serious, looking light and animated.

Antonio eats heartily — tearing off great hunks of bread, gulping wine, and answering questions between noisy slurps of soup.

He still looks travel-weary from the road, but scrubbed clean — thankfully, she notes. Though she can’t quite tell if his glow is from the washtub, or the relief of returning home. It has been well over a year since he had supped with them last, and he looks different now. At his age, a year can do much to change a face. But it isn’t only that. There is something else. A new kind of intensity.

Livia beams at the boys around her table.

At her side, Matteo sits coolly, holding himself in check, observing the traveller like a distant curiosity, a puzzle he’s not quite sure he wants to solve.

Antonio spoons more soup into his bowl, then leaning back in his chair, he launches into his story.

There’s a rehearsed quality to it, Livia can tell. He has the cadence of someone who’s already told it a dozen times, though he’s only been home a few days.

“The Jubilee,” he says, drawing the word out slowly, and with reverence, his eyes scanning his tiny audience.

Every year, pilgrims travelled to Rome, but never in such great numbers as for the Jubilee in 1400. They had followed the Via Francigena — the ancient road winding south, four weeks on foot — hundreds of them together, their sandals wearing thin over the long journey. Monks in travel-stained robes leading the way, walking in prayer and song. They carried their bedrolls on their backs, slept in monasteries and hospices along the road.

And then, at last, they arrived — footsore, dust-streaked and travel-worn — at the gates of the eternal city, the city of the Pope.

“A journey that cleanses the soul,” Antonio says in an awed whisper, trailing off.

Then his voice brightening.

“I wish that you could have seen it, the Ponte Sant'Angelo, flooded with pilgrims. So many people they formed a great river, split in two — one flowing in, pilgrims weary with the dust. Another flowing out, their souls scrubbed clean, and their faces shining.”

Antonio lets the image hang in the air.

Livia raises her goblet to her mouth to hide her wry smile. “That’ll explain it then,” she thinks. She looks to her husband, who has the furrowed brow of someone already planning his exit, but Filippo and Donato are leaning in with interest.

Antonio goes on.

He speaks of Saint Peter’s tomb. Of the bronze statue worn smooth by the kisses of the faithful. He speaks of praying over the bones of the martyrs, of touching the blackened links of the chains that had once held Saint Peter. Of the Pope’s seat — pale white marble patterned with terracotta and emerald stone inserts, empty — and plain, really — against all the gold leaf glittering around it.

And of the Pope himself, when they saw him, giving the blessing ‘Urbi et Orbi’ — to the city and to all the world.

Livia watches him closely. Watches the way the others lean in.

She hates that she feels this way, but the longer Antonio talks, the more uneasy she becomes. He has barely shaken the dust from his tunic, and already she can see him filling the room with the scent of the road, and she can see the effect he’s having on Filippo and Donato both, filling their heads with dreams of Rome — that lawless city.

With the soup growing cold, Livia rises, steadying with hands on the table, and excuses herself to the kitchen. From the pantry, she can hear their muffled voices. She gathers a heap of figs, halving them to expose their fleshy insides, adding a sprinkle of walnuts. Looking around, she chooses a pretty dish and begins slicing an apple into thin wedges.

In the dining room, Donato’s eyes sparkle with a question. His voice light, he asks: “Did you bring back any sketches?

“Oh, Yes,” Antonio reaches into his satchel, producing a small bundle of parchment, the pages worn, yellowed and rustling in his hand.

Donato reaches for them eagerly. “You sketched these yourself?” He asks, leaning forward on an elbow. “Do you have any drawings of the Pantheon?”

Antonio nods, pointing to a rough charcoal sketch. He runs a finger along the hint of a semicircle. “You can see the Pantheon in the distance — there” Reaching for his wine, he adds “That’s where Saint Peter — the very first Martyr, had been strung up and crucified upside down, not allowed the honour of —”

“ — Did you get inside?” Filippo interrupts, excitedly, “Did you see the Oculus?” his eyes scanning the sketch for clues. Then he flushes, ashamed. “Forgive me, Antonio,” and he shrugs.

Antonio waves it off, his smile tightening. “We did go inside,” he says “We prayed there —for Saint Peter” He pauses.

Something in his tone has changed, a flicker of disappointment crossing his face.

Matteo and his father having drifted into a soft conversation of their own, now begin trailing out of the room, entering the study, the door clicking shut behind them.

Donato finds a place where the parchment has folded over, and tries to straighten it out. “Just imagine, Pippo,” he whispers. “A dome so strong, it doesn’t even need to be closed — leaving a hole in the top, just because they could.” He chuckles, drawing a little halo in the air with his fingers, eyes widening.

Filippo laughs “As if they had meant to taunt Florence.” His eyes slanting towards the dome just beyond the iron grate — the lack of a dome, rather — except Filippo could sometimes see it, a red rose riding high above the rooftops. He could see it now.

Filippo looks to his father’s empty seat and then back to Antonio. “Do you have more sketches? Of the ruins?”

Antonio shrugs, irritated now “We passed them. The are ruins are everywhere. But we didn’t linger there.” His jaw tightens.

“You mean they warned you not to look too closely,” Filippo says, eyes narrowing, “In the Guild, we hear all about the accomplishments of Rome, they sing her praises, but when it comes to the actual measurements?” A sigh. “Rome sits in the sand, with her knowledge crumbling to dust and not one brave enough to dirty their hands.”

“Measurements?” Antonio spitting out the word, shifting in his seat. “They built idols, Filippo,” he hisses. “There is nothing to learn from them except vanity.”

“You sat in her churches, Antonio — did you not know that the stones beneath your knees were Roman?”

Antonio grows quiet. His words faltering. He sees it clearly now: He had mistaken the look in their eyes. They do not hunger for salvation — but only for ruin. These two did not invite him here to speak of relics or prayers, or pilgrims, or even the Holy Pope.

His jaw tightens.

The Ancient Romans had left behind their ruins — fragments of once-perfect forms. And Florence, unable to match her in skill, had instead dismissed her brilliance as excess, her mastery as idolatry. They deemed her too beautiful — technically perfect but spiritually empty.

The guilds, the scholars, the fathers of Florence — they had all agreed that the Rome of antiquity had flown far too close to the sun, and that this must surely have been the reason for her downfall: That the wax points holding her wings intact had melted, and along with bits of wing floating to the ground, so too came the Romans as they fell, tumbling into the earth.

And yet, every year, the builders of Florence would unearth her — Rome — in shards. Each time they turned the soil to lay new foundations, they found her again: in old marble columns, Latin words worn smooth by time.

Had they forgotten? That Florence herself was once Florentia, — a colony built on the bones of Rome, her marble fragments, glittering idols in the sand.

“You call Rome Icarus,” Filippo says, more quietly now. “But tell me, Antonio — do we not all strain for beauty?”

Unconsciously, he had lifted a calloused hand — past the open grate, to where the cathedral waits, unfinished, the proudest of them all. She waits, a ruin even before her completion.

Donato, desperate to lighten the mood, tries: “Well, I suppose we’ll be quoting Cicero before dessert.” He chuckles weakly.

Livia, returning with her apple slices, splayed out on a pretty plate, with the halved figs and walnuts, stands frozen in the doorway. “Well,” she says wryly, “it seems the conversation has livened up somewhat since I left.”

She places the fruit heavily, at the center of the table, glancing once more at her son, before settling back into her seat.

Somewhere, four weeks south of them by foot, a pale circle of moonlight falls through the oculus of the Pantheon — a searchlight through her aperture, the moon by night and the sun by day, casting around her hollow dome for the place where Saint Peter was said to have been crucified — not finding it. Still searching.

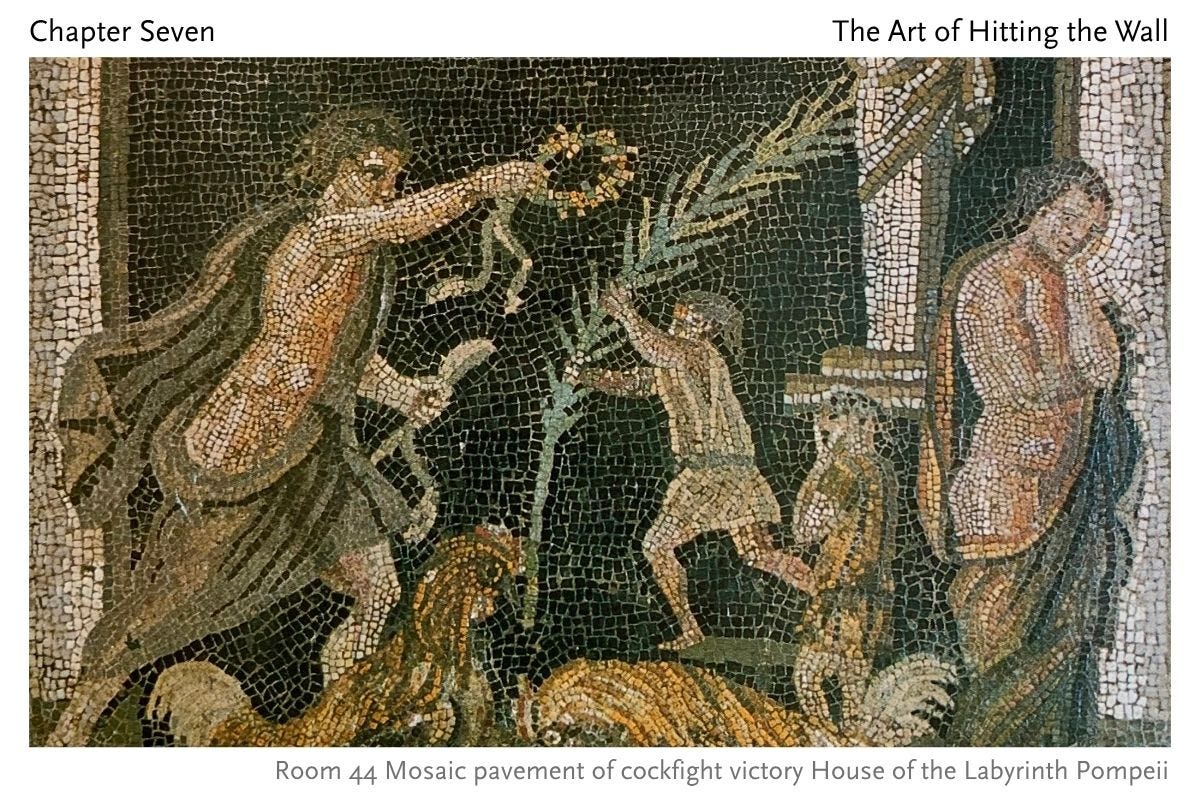

Image Credit:

Room 44 Mosaic pavement of cockfight victory House of the Labyrinth Pompeii, Mosaikausschnitt, Roman Villas in Karthago, 1st century CE

… through the eyes of Art History , a beautiful piece ❤️