Chapter 8: Beneath the Guilding

High over Tuscany, where the air is cool and crisp, a swallow is soaring on the afternoon currents. She follows the river north, a loose, winding ribbon of silver that catches the sunlight. Faint lines score the earth below — roads running northward from Siena. Thin smoke rises from the red roofs of Impruneta, a town that smells of baking terracotta all year round. Further to the north and east, the passes climb, winding into the Apennine mountains, and to the west, the bright distant shimmer of the ocean.

The swallow dips, gliding closer to a scatter of terracotta roofs, her black wings tapered into sharp tips. Her belly is as pale as chalk, her hood is midnight blue, gleaming as her feathers catch the sun. At her throat, the warm red rust of fired clay, as she trills her song on the air.

Her tail is dark, parted like the coat-tails of a rider, her chest held high, even as her bead-black eyes scan the river.

In a sudden swoop, she drops low, brushing one wingtip to lightly skim the surface of the Arno, leaving the faintest ripple — before she climbs again, banking over the Ponte Vecchio. She circles once above the cramped red rooftops, then drops lightly onto the warm clay tiles of a workshop roof, folding her wings tight to her sides as she comes to rest.

Below, on a workbench, where a stack of solid gold florins had been — each coin stamped with the image of Saint John the Baptist, each worth three pairs of good leather shoes or a mason’s week of wages — there is now only a low mound of fine metal filings. A hacksaw lies warm from use, its teeth grinning with bright gold swarf.

Beside it, a glass bottle from the apothecary, squat and weighty, sealed in wax. The label is inked in a careful Spanish hand: argento vivo — living silver — named for the way it slides and moves in the bottle, creeping along the glass as if alive.

Once the bottle’s wax seal is broken, the wing-footed Mercury is said to appear, standing just out of the edge of the goldsmith’s sight. He tugs gently, pulling with unseen hands, a thread — the lifeforce of the man who would dare to guild. When the thread runs out, Mercury will take him gently by the hand and guide his spirit to the underworld, or whatever lies waiting on the other side.

Filippo exhales through gritted teeth. And then — click. The wax gives way.

Now there is no turning back. He will work quickly to see it done, burned clean before nightfall, lest the vapours get him.

With great care, he tips the glass, the quicksilver, thick and heavy, a polished mirror that bends and shifts, as and when it wills.

Gold and poison do not wish to marry. The pestle circles round with the rough scrape of stone and still they resist one another. But the goldsmith persists, beating with mortar and pestle, the eight parts mercury to one part gold. And then slowly, and by degrees, as if accepting no way out, a softening, as the metals yield and take one another in.

The paste comes together thick as butter, a pale yellow-gray with a strange metallic weight. With a small brush, he lays it on swift and thick, deliberate, working the paste evenly over every rise and recess — coating the scene.

Across his face Filippo wears a damp, knotted cloth, a red line biting into the bridge of his nose where the linen rubs raw. A crease lines his forehead as he remembers the words of his tutor: “Do not breathe the vapours”. Easy enough to say looking over the faces of your students. Harder when the work is long and a man must breathe.

A sudden tilt in the clay floor tiles, gone as quickly as it came. He shakes it off, it is a tremor, nothing more. He straightens, touching the edge of his workbench, setting his jaw.

The problem is this: the vapours carry no strong scent. It's easy to forget. And when the guilder catches a sweetness on the air — it's already far too late. He hears a chuckle from deep inside his mind, or behind him in the workshop?

Who can say.

The furnace is modest, the heat kept low, easing the paste toward warmth. From its surface, mercury vapours rise, an almost imperceptible haze curling up, and up and —

A thud against rooftiles. Then a muffled roll. Something has dropped before the open door of his workshop.

It lies still. Feathered, with a rust-red throat.

Filippo's mouth forms a line. You picked the wrong roof, he thinks.

He does not move to the door. Let the bird keep it's place until nightfall — a small, fallen sentinel at his threshold warning anyone who might think to step inside.

Who knows where the vapours are curling now? Trailing along the floor, gathering in the corners? Soaking into rafters? Sinking into his skin?

At the furnace, the colour deepens with every pass through the heat, poison drifting off, delivering the gold on its way. Too much heat, too soon and the color will turn ashen.

He must work slowly. He must work fast.

Filippo's gaze slides upward, eyes narrowing into the rafters, willing no more birds —no more wings beating against the taint.

He wonders, not for the first time if that wing-footed god spared a thought for the souls of birds. Whether they awake wingless and needing to be carried into whatever murky depths lie beyond.

A light knock at his door. A figure stands at the threshold.

It is Livia, a woven basket balanced on her arm. Her expression is bright, but her eyes move quickly, catching on the bottle, the mortar, the furnace. Behind her, the day is warm, sunlit, the sky a pale blue — but its brightness does not reach him.

He turns sharply, the whites of his eyes showing. “Step away”, he snaps, pointing, “Can you not see?” His voice cracks.

He gestures again, to the limp bundle at the door.

She sets aside the basket. Then quietly, she leans to retrieve a small wrap of cloth. Filippo only stutters and glares up into the rafters, as if to unsee what his mother is doing. He will not argue with her. Gently she crouches, gathering the bird, tucking its wings snug to its belly and swaddles it, the way she once swaddled her children.

She looks up at him, her face tilts. “You’re looking pale,” she says.

“I’m fine,” he replies, too quickly. He waves a hand. “I’m almost done,” he lies.

She doesn’t answer. Just watches him. One long, level look that takes in the tautness in his shoulders, the way he leans on the bench with a hand to steady himself.

She knows the signs — knows that living silver brings on his dark, mercurial moods.

If I could, she thinks, I would drag him down to the banks of the river, make him eat something, let him breathe the clean air. Let the sunshine clear his head.

But she says nothing.

She knows that he is watching the daylight. Every minute spent with quicksilver evaporating in his workshop — she will not add to the danger.

Instead, she lets out the faintest sigh and lifts the lid of the basket.

“There’s bread,” she had smeared it with plenty of garlic, “a little bit of cheese, juniper berries — to cleanse the blood,” she says. “Promise me you’ll eat”.

Not waiting for a reply, she stands, touching the earth lightly as she rises to her feet. The dead swallow rests in her soft hand as if it is only sleeping.

Her eyes sweep once more over the workshop. Her quick smile does not reach her eyes, and a moment later, she has gone.

A few more passes through the furnace and at last, what emerges is the warm gold of honey, a thin brilliant layer, bonded to the metal but not yet gleaming — still rough.

A dull ringing settles into the space between his ears. He blinks. It will pass.

The final step takes days.

Filippo works slowly, bent over and silent, pressing the rough gold surface smooth — with agate, bloodstone and dog’s tooth, each chosen for it’s particular shape and bite.

His back aches and his knuckles stiffen.

The work is a kind of prayer.

He falls into a rhythm older than thought — pressure and release, pressure and release — until the scene begins to bloom. The gold surface smooths to a mirror sheen, with a radiance that catches the light like still water at sunrise.

And Filippo, the priest of this unlikely temple, kneeling at his altar with a ritual that has passed through centuries of makers — and passes through us still — has baptised his scene in gold.

It is radiant, concealing all the pain and sacrifice it took to make it so. The polish seals it in forever, the sweat and the time and the effort. He had pushed it down until all that remained was a surface so bright, so seamlessly perfect, that it could fool the eye into believing it had been effortless.

A simple scene from the book of Moses.

He covers it in a wrap of plain white linen. He packs a cart with straw, as the porters do, and carts it, wheels creaking and protesting loudly — to those proud doors of the Arte della Seta with his head held high, as if it weighed nothing at all.

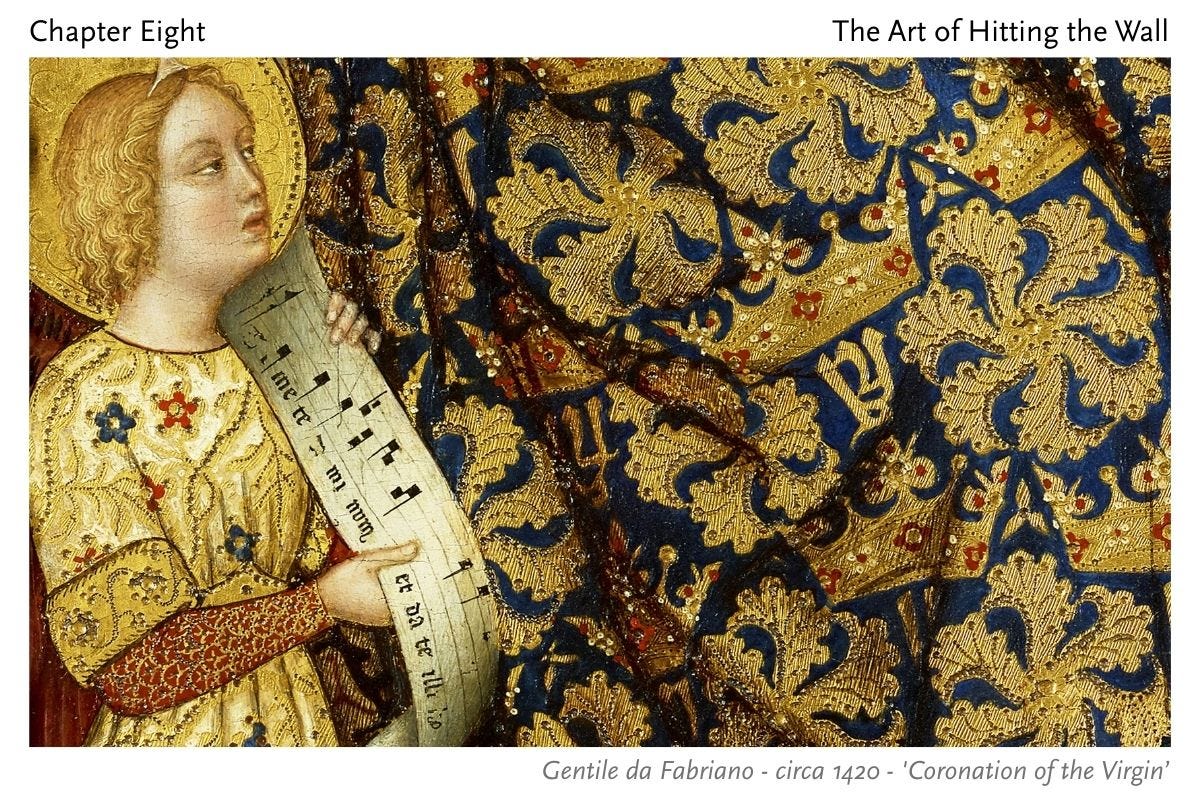

Image Credit:

Gentile da Fabriano, circa 1420, ‘Coronation of the Virgin’

Image courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum.

What a labor of love and what an involved process 🤩