Chapter 9: The Waiting and the Whispers

There had been many Florences.

The first, Florentia, had been founded in the first Century BC as a Roman military camp. Her shape, scratched in the earth with a soldier’s precision, a tight square pressed between the Arno and the place where the great cathedral would one day rise. Her streets ran straight, crossing at right angles. A man could walk her length, from wall to wall in minutes, as she defended the ones who had built her, and those who came after.

But Florence would not stay small. Her walls groaned with the press of people until they burst outward, and the builders poured themselves into the fields, stacking stone upon stone, raising up a new wall with its towers and gates. And once each was guarded to keep the danger out, the old Roman walls were torn away, and Florence unfurled, settling into her new skin.

It happened again and again. In the twelfth century as wealth poured in, Florence spread outwards to gather the bankers, the merchants and the markets. In the fourteenth, Arnolfo’s wall reached farther still, encompassing orchards, monasteries and farmlands. That wall had taken fifty years to build — eight and a half kilometers of stone now encircled the city, crowned with seventy towers and six great gates.

And so it was that five Florences had grown, each nested inside the other like the rings of an ancient tree — each wall a circle of stone to hold her people near.

Now, beyond the press of the city’s centre, far from that Roman grid, the cobbled streets give way to winding lanes that dip and bend through the outskirts, their ruts holding the last of the rain, and the air smelling of tilled soil. Some roads are lined with the tall dark spires of cypress trees, others with blackberry thickets where thrushes and blackbirds quarrel over the last berries of summer.

Here, near the edge of Florence’s last embrace, stands a tiny house with its roof patched in a quilt of reds and browns. Late-afternoon light slants through the leaves, dappling the grass with shade and gold. A cool breeze stirs the branches. The trees bend low under their burden of ripened fruit, the scent of straw mingling with the sweet rot of fallen plums as lambs nose through the shadows, bleating contentedly.

Beside the house, a rough shelter for sheep, its open side letting the animals wander freely in and out. The wind whistles faintly through the gaps in its wooden slats. Inside, the earth is bare and trampled, ringed with dark circles where buckets once stood. Along the wall, a pair of great iron shears, wool combs with their long wire teeth, hayforks, nets, and bales of straw, stacked and leaning against the raw timber beams.

At a rickety table in the centre, a boy stoops over a lump of red earth. His stained fingers working the clay into form, shaping and smoothing, then stops. Stepping back a pace with head tilting, as if to test the figure from another angle, his eyes narrow. For a moment he stands still, a frown. Then, back to work as he moves in again, his hands quick and sure, the clay yielding to the scrape of his tools.

A lamb nudges between Donato and his bucket of muddy water, and without looking, he shoos it away, brushing the fleece with the back of his hand.

From the cottage, his father appears, trudging across the yard with a wooden stool in one hand and a bucket of raw wool in the other. His grey curls catch silver in the light as he lowers himself onto the stool with a grateful exhale and wipes his hands on his apron. From the city a bell tolls, the sound carrying faint and hollow over the fields. Berto glances toward the distant city wall, its stone line cutting the horizon, before settling back on his son.

“I wonder what their excuse is now?” mutters Donato, half to himself.

The judgement was late. It should have come months ago, back when the sheep were being shorn and the air was full of pink plum blossoms. Now the season had turned, the fruit grown heavy, and still they were waiting.

There had been plague the previous year, and some said it had upset the guild business. Others whispered that the judges needed more time — that the votes were split between two favourites, Ghiberti and Filippo.

Only whispers.

Berto, looking into his pail of wool, raises his hand absently, and Donato turns to the wall to pick out the wool combs, placing them in his father's palm.

“But 34 judges,” Donato turns, shaking his head, incredulous, “and no decision yet?”

“Aye.” Berto sighs, drawing the wool through the teeth with slow, even strokes. “That Filippo is a master, for sure,” he chuckles, “but he’ll not bow to a committee. Can you imagine Filippo being told to bring out his sketches, so they can haggle over his design? Berto cracks into a laugh, his eyes glinting. “A man like that can’t be steered, you see?”

“And Ghiberti?” asks Donato, shoving a sleeve back up his arm with clay-damp fingers.

Berto’s hands keep their rhythm, comb rasping through the wool. “That one’s a talker. But he's thrifty, you see. He’ll use less bronze. He’ll weigh it like flour if it saves him a florin. The guild will like that.”

Donato scowls. “What are they judging? The man or the bronze?”

Berto’s face shifts, serious now, distant, as though his answer had come from hard-earned knowing. “Aye. That’s the right question.”

Impatience flickers in Donato’s eyes.

Berto sees it. The city would take its time; the guilds always did. But he knows the waiting gnaws at the boy. For himself, he’s been enjoying these long afternoons, his son working beside him, but he knows such days won’t last.

Donato’s youth is restless. He wants his future to begin.

“Well then, my Donato,” Berto says, slapping his knee with a grin, “you’ve played your cards well. If Ghiberti wins, you’ll have a place working in his workshop.” He leans closer, his voice warm, conspiratorial. “And if Filippo wins, you'll be needed in his.” He leans back on his stool, contented.

Donato’s attention doesn't leave the clay figure, but his mouth curls into a grin he can’t suppress.

“And maybe then,” Berto adds, laughter rumbling in his throat, “you’ll stop banging about in my shed, frightening the flock.”

Two boys tear down the muddy path, their bare feet splashing through puddles that mirror the pale blue sky. Their shouts carry on the cooling air, sharp as swallows cutting across the fields. Wandering chickens scatter with indignant clucks as Piero and Niccolò charge past, their cheeks flushed.

They are playing out a story they had heard.

The Trojan horse arrives at the city walls — a vast wooden structure, her timbers groaning. Except in their imagining, she does not come rolling up on wheels but floats up the Arno, her heavy flanks scraping the stone embankments, barnacled boards dripping with weed. Slowly, she noses against the arches of the Ponte Vecchio. She can go no further — for the bridge.

From deep inside her hull, a voice booms. Piero cups his hands around his mouth, his chest swells as he makes the words carry, echoing through the belly of the beast: “We bring you a gift. Let us in.”

And he grins wide, watching for his brother’s response.

Niccolò knows his part well. He gasps, clutching at his throat. He can hear them, the shuffle of a hundred blades of steel, glinting in the dark. His eyes widen.

He points, “It is a trap. Can’t you see?”

Piero swings around, his affect changed, his voice a high falsetto, hands clasped in mock delight. “Oh, wonderful,” He is speaking for the priests, and counselors, and merchants fat with coin — nodding and smiling, dazzled by a gift. Piero signals, “Let her in!” They see only the timber, and not the steel within.

“No! Send her away!” Niccolò shouts, stamping in the mud. “She is sent from our enemies,” he pleads.

“They can’t hear you, Niccolò.” Piero goes on, his voice dripping with disdain as he solemnly shakes his head.

“It’s a trap!” Niccolò shouts, shaking his fists in mock frustration. He whips an arm behind his back and pulls out an invisible spear, hurling it at the Trojan horse. “A spear through your wooden belly” he crows, triumphant.

Piero’s expression hardens. Slowly he raises his arms, mimicking the solemn judge, a finger pointed straight at his brother. Sentencing the messenger.

“Run!” Piero bellows.

Niccolò spins in the damp earth, already stumbling forward. He runs, his little legs racing to carry him, his brother on his heels.

“A slithering snake has your right arm!” Piero calls. Niccolò jerks his right arm stiff, running lopsided with one arm dangling in the air.

“A snake has got your left leg!” Calls Piero, laughing now, as Niccolò begins to hop wildly on the other.

“Now it has your right leg too!” calls Piero, running to catch up.

Niccolò skids to a stop and spins, turning to question his brother. “Wait, what happens if I lose?” Niccolò shouts, breathless.

“You turn to stone!” Piero whispers sharply, eyes wide.

“And what must I do to win?”

Piero’s eyes flash, his voice sharp as a trumpet. “You must run faster!”

And the two of them bolt beneath the fruit trees, shrieking, the puddles splashing underfoot as they flee from the wooden horse that only they can see.

Donato and his father watch as the boys’ game spills into the orchard, their shouts carrying through the trees.

Berto gives a scandalised shake of his head. “If their mother had overheard such play, she’d have crossed herself and rinsed their ears with vinegar for speaking of pagan things.” He chuckled despite himself, the lines at his eyes crinkling. “Where would they have heard such a story as this?”

“Better they stick to tales of saints and martyrs,” Donato shrugs. But he knows where they got this story, for he had heard it too.

Not in the classroom, where such tales were forbidden — but after class, his tutor, noticing his talent for shaping clay, had leaned in close, lowering his voice with a story: “Somewhere in Rome, lost,” he had said, “it had been written that there was once a stood a statue greater than any other in the world, stone so lifelike it might draw breath. Of Laocoön, the priest of Troy and his two sons, caught in the coils of serpents.

Donato had tried to picture it: Laocoön, who had warned Troy of the trap, raising his spear against the fateful timber horse when no one else would listen. For his truth he was punished, by his own people and by the gods, struck down as the serpents dragged him under — him and his two young sons.

The words rang in Donato’s mind. He had seen fragments of Roman statues, broken pieces, wondrous things. He closed his eyes and tried to imagine marble veins tightening beneath the skin, in the moment before that serpent’s strike.

Long after he had heard the story, whenever he saw a shard of marble unearthed from the ground, one thought came first to him: Laocoön.

The boys’ game runs on until Piero’s interest wanes and he declares that his brother has finally outrun the serpents. The boys turn back together, triumphant saviors of Florence once more, their laughter spilling into the orchard as the sun dips behind the wall casting a shadow that stretches a widening band of darkness at the city’s edge.

As the orchard sinks into shadow, the taverns begin to murmur. In the dark of the city, merchants lean over their cups of wine, whispers passing from one to another.

Had Ghiberti been seen in candlelit chambers, with judges and guild members, speaking softly, of votes not yet cast but already promised?

Some swore they had glimpsed him, a hand resting easily on a guild member’s arm, eyes half-lidded in conspiracy. Others swore it was only invention.

Still, the whispers spread, threading through the alleys, curling beneath the doors of guild halls, and winding their way through Florence. The city herself seemed to lean inward, her stone walls straining to listen.

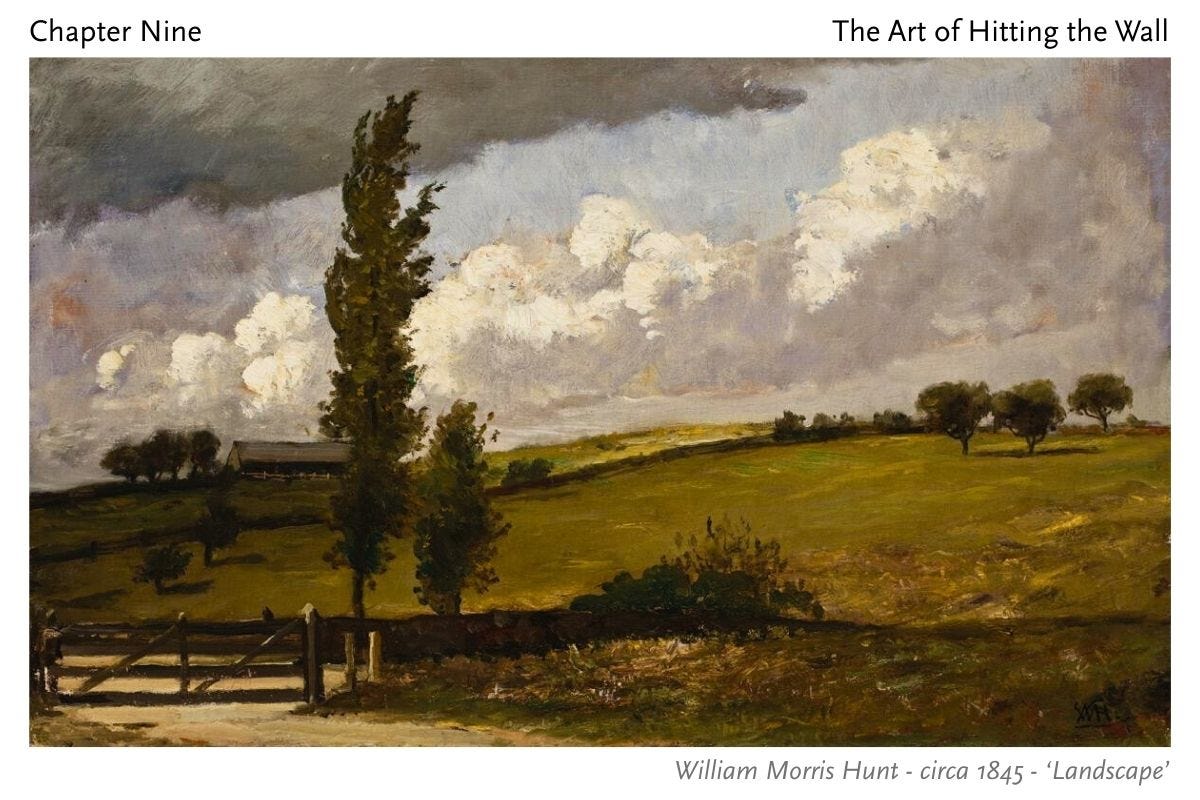

Image Credit:

William Morris Hunt - circa 1845 - ‘Landscape,’ Credit Worcester Art Museum