Chapter 5: Out of the Fragments

I step out of the coffee shop onto Terrace Street. The steep slope tips me forward, as warm light glints off the windows of Wellington’s modest office blocks. Pōhutukawa trees line the street, their crimson blooms bristling like pincushions, catching in the warm afternoon light.

I’m in my summer staples: a floral blouse, casual jeans, and sensible shoes, my handbag slung over one shoulder. In long, easy strides, I let gravity carry me downhill toward Woodward Street, where I’ll slip into the bustle of Lambton Quay and catch my bus home.

I arrive to find Carl in the yard, pumping up his mountain bike tires. He’s dressed in his riding gear — all in black; shorts and knee-guards.

“I’m going for a ride with Chris,” he says, and then he glances up at the sky, as if gauging how much daylight he has left.

At street level, Wellington seems to be a city pressed flush against the harbour — but as you climb into the hills, it quickly turns wild. Forests take over, with tramping tracks and biking trails, ridgelines and footpaths threaded like pale veins through the green. Wellington belongs to the bikers and trail runners above — the adventurous of spirit, who catch only fleeting glimpses of the city as it sinks into the valleys below.

Carl is buzzing around me, making trips to the car, carrying his bike, grabbing his helmet, his water bottle, a snack from the kitchen. I see him off and then I close the door behind me, to silence.

And in the abrupt stillness, it lands on me again — that single thought that always seems to hover nearby, waiting for me in the quiet:

I have an essay to write.

The Impressionists won’t leave me be.

I fix myself a mug of coffee and sink into the couch.

An idea is a beautiful thing. Pure and weightless, it doesn’t yet live in three-dimensional space, where it might crack, warp or crumple under pressure. It floats, unbound by the laws of physics, unbothered by time, and unconstrained by the limits of possibility.

This is why the first step is always so hard. Because the moment you start building the dream, the illusion must shatter.

I take out an old tin geometry set, and pick out the short, clear plastic ruler. I draw a clean pencil line from left to right across the page.

This is the timeline.

Traditional arts on the left: Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassicism.

Modernism on the right: Impressionism, and all the other "isms" that followed in its wake: Cubism and Surrealism.

In roughly the middle of the line, I press down, marking a moment in the timeline that seems to draw my attention above all else. It’s a turning point of my story — the Salon des Refusés in Paris, in the early summer of 1863.

I imagine them:

A crowd gathers outside the Palais de l’Industrie, its grand stone façade rising above the banks of the Seine. They’re dressed in their Parisian best, fanning themselves, shading their eyes from the mid-morning sun. The air is humid, the crowd full of restless energy, curious and murmuring.

Each year, the Académie des Beaux-Arts presents its finest artworks at the Institut de France, a short carriage ride away from here. But the pile of rejections has been growing year by year — thousands of entries.

And now, for the first time, the public has been invited to see what’s been hidden from them — a special exhibition to showcase all the artworks that had been refused by the Académie.

The Salon des Refusés.

The crowd forms a line that wraps around the building, lining up to view what was deemed ‘unfit’ — paintings that defied the rules of proportion, works with brushstrokes that are too visible, too unrealistic—too expressive.

A woman stands in the queue, parasol in a gloved hand. She stares across the river Seine, looking faintly amused. She is already scoffing at the idea of the paintings that she will see inside, though she hasn’t seen them yet. She knows what ‘good’ art looks like and “this is not it,” she is preparing to say. A man near the front scans the posters, looking for names he might recognise. Another peers upward at the wide entrance of the building, wondering what sort of art could be so wrong—so dangerous, that it had to be hidden from public view.

It’s fun to open a history book and see the players take their positions and play out a story of what happened long ago. A symphony of logical steps & neat progressions, as if the people of the past knew the choreography by heart.

As if it was all inevitable.

I reach over to take a sip of my coffee and take a bite of an oaty digestive biscuit, crumbs falling into my lap. I pick out the crumbs and place them on a little plate beside me.

My notch in the timeline sits alone.

I add another, just a fingertip’s space to the left, 25 years earlier.

If my first notch was for the artists, this one is for the camera:

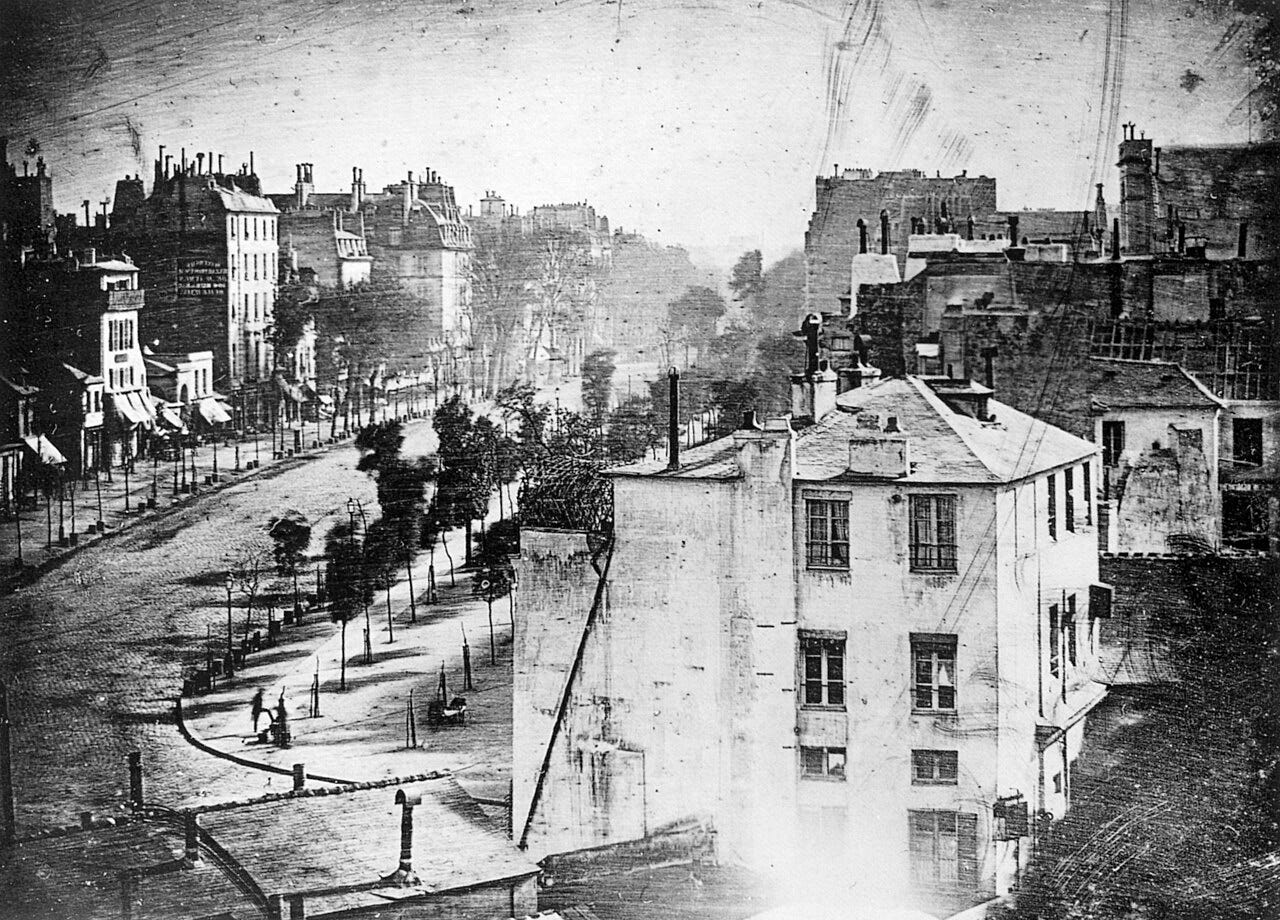

It’s Paris again, in the spring of 1838.

From an open window, a camera stands fixed on a windowsill, a large wooden box with ornate brass fittings, looking out on the boulevard below.

It’s just after 8am, and the city bustles with horses and carts that clatter over the cobblestones, street vendors calling out, and people streaming along the sidewalks, hurrying to work.

The camera is silently working, a sliver of light entering through a tiny aperture, projecting the scene outside onto a light-sensitive plate of polished silver. For six long minutes, the camera watches, as the silver plate gradually absorbs the light, burning an image, faint at first, then growing stronger.

When the photograph is finally developed, the street in the picture appears empty, though the street outside is still bustling. The crowds had places to get to, moving quickly, their forms passing like ghosts — the lens forgetting them.

But look again and you’ll see two figures, small, in the lower left corner. One man stands, his boot propped on a platform. Another crouches before him, a cloth in his hand. A shoe-shiner and his client, frozen in place long enough to become real.

This is the first known photograph of a person. Two of them. The street had been full that morning — but only these two stayed still long enough to leave a mark.

These two pencil notches perch side-by-side on my timeline, and then more descending, like birds coming to land on a telephone wire.

Drawing a straight line is easy enough.

It’s only when I start pouring the story in, that it begins to swell, bulging outward like wet clay. The essay, once so elegant in my mind, begins to groan.

For every detail I add to my timeline, a voice: “Not only that. Don’t tell half-truths.”

It wasn’t just the camera, it didn’t arrive alone. It came alongside the factories, the railways, the Industrial Revolution.

It was Darwin, scribbling On the Origin of Species. Freud, cracking open the psyche. It was the atom. The telegraph. The revolution.

A thousand things, all at once.

All of it pushing us inward, in toward a different way of seeing the world.

But what were they pushing off from? What was the shape of the world they were leaving behind?

“The essayist is a liar,” I smirk, “because he knows the arguments for and against his case, but he will not hand them over.

He arrives with an agenda and it may be for good or ill, but he cannot paint you a full picture, because the medium itself is limited.

So he reaches for a sewing needle, and through its narrow eye, he tells you only the details that line up perfectly with his point.”

I laugh at myself.

This is my excuse, of course, for the fact that my first draft is reaching 8000 words and makes no sense. It also explains why last week’s laundry isn’t folded, there’s a pile of dishes in the sink and my coffee is cold.

But still — I must tell you about the Renaissance.

I scribble three words that capture the spirit of the Renaissance.

Order, beauty, knowledge.

I let them ring like a bell in my ear.

But as I look at them on the page, they look somehow hollow, flat and empty.

I am constructing a cardboard cutout of the Renaissance — one that will fall over as soon as the wind blows.

If I want to paint you the turning point with all its colour and drama, I must first paint you a Renaissance that makes you want to tip headfirst into it. She must capture your heart before we tear her down.

She must protest — or the whole story loses its meaning.

I keep adding more, hoping that the details will bring it to life, but the more I pour in, the more it reads like a textbook.

And I hear Mrs Collette’s voice echoing in my head:

“Thumbs, Tara, Too heavy in the thumbs.”

I look at what I’ve written — the sprawling mess of it.

I highlight all the text, pause,

and click delete.

The cursor blinks at me from a page that’s suddenly clean, crisp and white.

It blinks at me, expectant.

The light in the living room is dimming now. Evening has crept in, unnoticed. I move through the rooms turning on lights and drawing the curtains closed — feeling defeated.

Then I return to my laptop.

This time, from a blank page, I start planning, a short, simple piece about making space for fragile ideas. About granting yourself permission. About how the creative process is often real and ugly and messy — and that’s okay.

It was my attempt to offer a kind of bone-deep permission to the reader — to start anyway. I thought I was writing it for someone else.

But what I didn’t know then was that the person I was giving permission to, was me.

The tiles underfoot are parquet, laid in small interlocking squares of wood. I’m running to fetch Granny’s reading glasses — the ones with the pink frames — so she can read the article my mom is pointing to in a magazine.

The couches are brown, the curtains, the crochet tablecloths, the walls are all shades of cream, yellowed by years of cigarette smoke.

In the corner of the room, a delicious monster leans up the wall, its leaves huge and glossy, as if it had grown straight out of a storybook.

Ryan and I are hanging over the back of the couch, now, peering out through the verandah window at the street outside. The bougainvillea spills out across the eaves, framing the view in green and bursts of bright magenta. The game is simple - we’re guessing the colour of the next car that will pass — and the one after that: Blue. Red. White.

Returning to the Casio keyboard which is balanced on the round dining table, I play ‘Groovy Kind of Love’ by Phil Collins. I try to play it softly, but Granny turns the volume right up, the notes spilling out, loud and tinny, from the plastic speakers.

She’s perched on the single-seater couch, her oversized pink t-shirt skimming her knees. Turned toward me, she is listening attentively, her blue-veined bare feet tucked beneath her as she rocks gently from side to side, to the time of my moving ballad, her chin lifted, lips puckered in exaggerated expression of delight.

I’m playing with the fingers of a child, one finger at a time, clunky — every note emphasised. I reach the end of the chorus, then play the verse again. Then the chorus. Round and round. I don’t know how to end it — so I stop abruptly.

Granny swoons and claps, enthusiastically.

“You play with such feeling!” she says.

I beam.

“Would you like some apple pie?” she asks. “I’ve got ice cream.”

Later, when we’re leaving — “before the traffic,” my mom insists — we begin our dance. It’s like this every time.

Granny says, “You must take some pea soup. I’ve got a container in the freezer — take the big one.”

“Ryan, this jacket will fit you. A little big in the shoulders, but you’ll grow into it.”

“Tara, don’t you want to take these magazines? I’ve read them all — I don’t need them.”

“Oh! The apple pie — there’s far too much. You must take some apple pie.”

Arms laden, we hug her goodbye, uncomfortable now, arms full of everything Granny has to give us — things she simply must give us, all of it pressed into our arms.

Her urgency is insistent. I laugh, because I do not understand it, that insistence. It’s as if she wants to give herself to us, in this tub of pea soup, in this slice of apple pie.

We eventually leave Granny's house in the thick of rush hour. My mom rests both hands on top of the steering wheel as we inch forward, pressed in among a sea of brake lights — the cars heading home from work. The car is quiet now, but in my lap, a warm slice of apple-pie — a grandmother’s love wrapped in cling film.

Before humans developed language, everything they learned stayed trapped inside their own skulls, and when they died, it all died with them.

How to sharpen a stick without driving splinters into your fingertips. How to notice the way birds circled differently when there was an injured zebra nearby.

Without language, none of it could be passed on.

But once we found ways to speak, the thread began to carry from one to another. It was still a fragile thing, easily broken — but at least now, it could be carried.

I am trying to give you a slice of my heart.

It’s full of beautiful paintings and music and poetry, and half-formed thoughts — looping into strange, and beautiful shapes.

Please take some.

I can’t hold it all on my own.

I am at my laptop again. This time, I’m collecting paintings — examples from each era.

I find myself reaching for the strongest examples — the classics — because they communicate the spirit of their movements so clearly. But theirs is only part of the story.

There are so many more: artists whose work doesn’t neatly represent the movement they’re in, or whose style was entirely their own, or hard to categorise.

If you only see the classics, it seems as though the pool of art is shallower than it is. But we’re swimming in art.

I look up from my computer screen, glancing around the room. White walls, light grey curtains, a light grey couch. No paintings adorn my walls. The palette is safe and minimal — It doesn’t make any bold statements.

I start to think about all the artworks that I can’t tell you about because there’s only so much space in an essay — just a thimbleful.

Then I begin to think about the artworks that I couldn’t tell you about because they have been lost in wars and fires, and floods.

And more than that — the ones that were never shared at all. How many artists cowered under their brilliance, afraid of being mocked? How many without access to the right connections? How many women overlooked?

History remembers the winners, the risk-takers, the lucky, the sure, and throws out the rest without ceremony.

And the ones who try to pour every drop of themselves into their project until the thing collapsed.

How many artworks lost to fires, I wonder — and how many times it was the artist themselves who struck the match.

Historians paint with fragments — shards of what people have committed to paper, stitched together from the ruins of what has survived.

They paint not in living technicolour — merely glimmers of what might have been.

If only there were a room — a kind of Salon des Refusés for the lost and the overlooked. A place where all of our forgotten works of art were stacked high, frame upon frame, leaning against the walls, waiting. And that we could demand to see them.

I’d queue for days, to see that exhibition. I’d go looking for something I recognise. Something dimly remembered — maybe even something of my own.

It is here that I am sitting, among the fragments now. An essay in ruins.

And maybe, there is no more fitting place from which to tell you the story of Florence — and the birth of the Renaissance — than here, among the fragments of something failed, and broken.

After all, the Renaissance herself was born, beneath an open sky, among the ruins of a lofty ambition.

Image Credits:

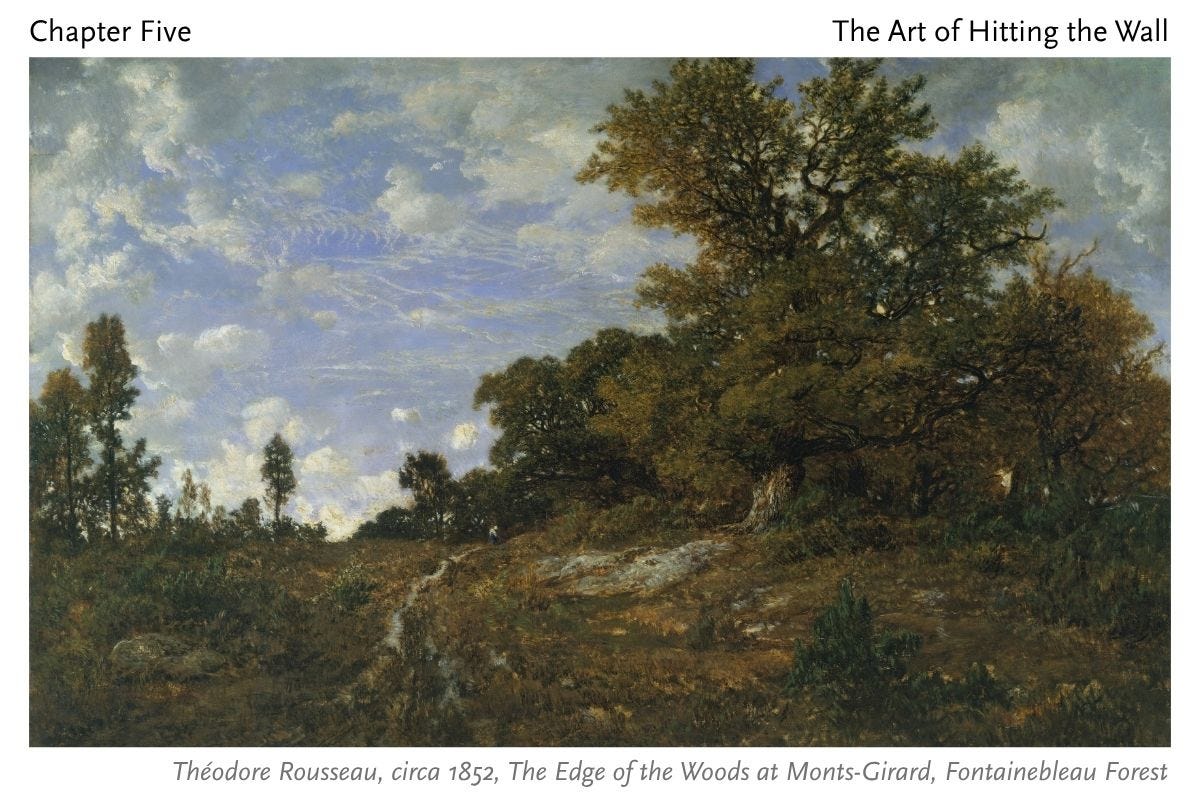

Théodore Rousseau, circa 1852, The Edge of the Woods at Monts-Girard, Fontainebleau Forest, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3rd arrondissement, Daguerreotype. Made in 1838 by inventor Louis Daguerre

I remember queuing in wet London snow for an hour to see an exhibition of the Impressionists and as I walked into the first room there were these paintings, so bright and colourful, that it seemed like one was looking through windows into summer scenery.