Chapter 1: Arrivals

All I wanted to do was write an essay about the impressionists. I did not ask them

to descend on me and ransack my house. “Oh?,” said my heart, “I think you did.”

I arrive to a morning already in motion. The coworking space is a cocoon of warmth and brightness — energising against the grey drizzle outside. But I barely register any of it as I drop my handbag on the desk with a thump, lost in thought.

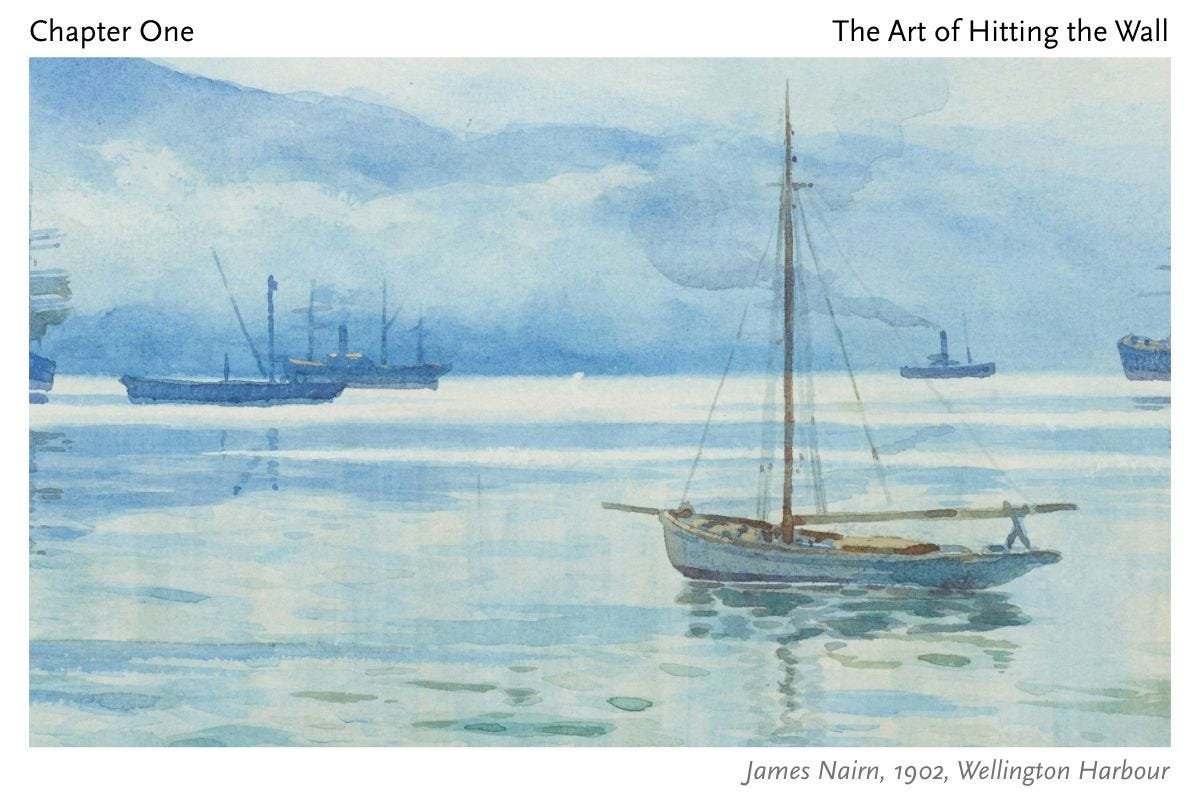

The office is a quiet modern space perched on the edge of the city, overlooking the wide grey-blue sweep of Wellington’s waterfront. This morning’s view is softened by a haze of droplets against the clear glass.

The days here move in an easy rhythm: low murmurs of conversation rise and dissolve into hushed stillness, muffled laughter drifting now and then from nearby offices.

I shrug off my coat and open my laptop, my mind already occupied with the three most important tasks of the day. I am turning them over, trying to decide which one needs my attention first and, caught in a moment of indecision, I find myself reaching for my phone, thumb already scrolling, defaulting to the comfort of distraction.

That’s when I see it.

It’s an essay by an artist I know — a piece written in a pleading tone:

“AI poses a very real threat to artists everywhere, threatening their work, their value, and the very meaning of art itself.”

I’ve heard this argument everywhere lately, so I am unprepared for the sudden wave of frustration that rises up in me.

“I spent years honing my craft,” it reads. “But if beautiful art can be generated with a click, then what is left for us?” I recognise the fear beneath it, and the concern is a valid one, but I feel my chest tighten with involuntary annoyance.

“This is ridiculous!” I snap. “It’s pointless raising your fist against the machine, hoping it will just go away.” My agitation feels out of place in the relaxed atmosphere.

When something unsettles me, my instinct is to fly straight into problem-solving mode – to restore order and resolve the dissonance as quickly as possible. Restless, I put down my phone and walk to the coffee machine. It hisses to life, steam feathering up in the morning air. Cradling my flat white, I make my way over to the big office windows, the waterfront stretching wide before me.

A calm wind gently smudges the shifting dimpled surface of the Pacific as small vessels mill about the bay, crossing each other in the middle distance.

Further out, an Air New Zealand plane with its distinctive black and white patterned tail is descending through the soft rain, wheels extending in its slow, deliberate approach. It hovers on the edge of arrival and then, just before touchdown, the plane slips behind the dark curve of Mount Victoria, disappearing from my view — leaving the moment unfinished, the landing happening somewhere out of sight.

I stand for a long moment, my gaze resting in the negative space.

Sometimes, the events of today carry a texture that feels strangely familiar — as if another time in history has lurched into orbit with our own, and the distance between then and now thins. The players of that time stop feeling like unknowable characters, and you begin to imagine you can feel the weight of their questions.

The Impressionists had been circling for weeks, at the edges of my mind in a wide, holding pattern, so when I reached for a story that might resolve the unease I was feeling, they came into view.

They were, after all, artists coming to blows with the technology of their day, just like us.

I began to wonder what it must have felt like to live through the disruption of the 1870s. The camera was gaining popularity, and suddenly you could recreate what the eye could see without the need for human hands. At the same time, the rigid standards of precision and order in art, which had held firm for centuries, were beginning to unravel. A group of artists in Paris were making waves, breaking with the Traditional arts. People at the time mocked them. “They have no skill,” the critics said.

For those who held firmly with the values of their day, it must have felt as if the very foundations of art were crumbling before their eyes.

But from where we stand today, the Impressionists overcame the gatekeepers of art and beauty, offering us a richer, more expansive concept of what art could be. Perhaps, when the camera freed human hands from the burden of depicting the world so accurately, artists could finally reach for new ways of seeing.

“Technology gave them their wings to fly,” I smiled hopefully, and tapping my pencil against the side of my coffee cup triumphantly, I felt like I had already solved it: I would write the essay — a neat parallel to our time, paired with an inspiring and hopeful message.

Very on brand for me.

But looking back, it reflected a kind of positivity that was only skin deep. “It’s never that simple.” Still, it would serve as my contribution on the topic and settle the uncomfortable feeling that was gnawing at the back of my mind.

The shift from Traditional to Modernist art is abrupt. You walk through a doorway from one room in an art gallery to the next — and everything changes. The Impressionist moment has always filled me with a strange sense of awe. The paintings are full of weather, as if someone opened a door and the art world wandered outside, blinking into the dappled light, the drifting clouds, and the swirling wind.

How did it feel to shatter the precision of the traditional arts; to walk away from centuries of mastery and step into a completely new era?

I thought I was only pulling on questions about art history and its resonance with our present moment. I didn’t know that the thread I was tugging on would run so deep that it would crack me open.

“Good news,” my doctor said, her voice warm and reassuring on the line. “I’ve got the results of your MRI, chest X-ray, and ultrasound — it’s all clear”

“Great,” I said, trying to sound relieved. “Nothing to worry about, then.” Except I’d had a sensation of a lump in my throat for weeks, a tight, unmoving knot at the base of my throat, as if a pebble had settled there and refused to dissolve.

And now, with this news, I was supposed to be feeling relief.

Instead, I open my laptop again and check my emails. While I had been away from my desk, my three urgent tasks had become four.

The Impressionists would have to wait.

8 Years Ago

In 2017, I left South Africa — the only home I’d ever known — and moved across the world to New Zealand with my fiancé, Carl. He had just accepted a job offer in Wellington, and within two months, we were packing up our lives and preparing to move eleven thousand kilometers away, across the Indian Ocean.

We had shipped some of our belongings to our new address, but those wouldn’t be arriving for another nine months. That meant one big suitcase and a carry-on would have to be enough for a while.

So what do you pack?

My laptop, of course, and our Egyptian cotton sheets. And what about my books? I tried to whittle down the towering collection I’d spent years building.

When that proved impossible, I picked three precious volumes I couldn’t bear to leave behind: a vegetarian cookbook, and two large history books, both by Peter Watson — ‘A History from Fire to Freud’ (That had me covered for early human history) and ‘A Terrible Beauty’, (a history of the twentieth Century).

Now, looking back, I see what I was really doing. I was trying to hold on to something solid and true in the shock of moving to a new country where everything else would feel unfamiliar. In my own way, I was trying to carry the whole human story with me — the comfort of being able to hold the whole world in my hands.

Image Credit: Wellington Harbour, 1902, by James Nairn. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

This is so incredible. Cannot wait for chapter 2 - when is it coming?

Just managed to catch up. (Friday morning and the server is down) no better time. ❤️