Chapter 6: Beneath an Open Sky

The rain is falling heavily over Florence. Fat drops strike the terracotta roof tiles, cascading, and tumbling from the eaves above onto the cobbled streets below. Water gathers in the grooves between cobblestones, twisting into silver ribbons that race through the narrow streets, downhill toward the wide river Arno.

Most of Florence’s inhabitants are dry, behind wooden shutters, or huddled beneath stone arches, waiting out the worst of it. But two young boys are running through the downpour, their tunics soaked and clinging, curls plastered to their foreheads, braided belts jostling with every footfall. Each boy carries a bundle of tools wrapped in waxed canvas, but today they serve only to weigh them down.

They have come too far to turn back now.

Rounding a corner, they burst onto the city square, and all at once she rises before them — the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, her patterned walls shining like wet silk. The storm-deepened sky casts the white marble in faint turquoise, drawing out the green stone details as if she had just emerged from an underwater scene.

The two boys push open the heavy doors and step out of the storm.

For a moment, they are on the edge of shared laughter in the giddy relief of escaping the cold rain, but the vastness of the grand interior, imposing, presses them back into silence.

Inside, the cathedral is mostly empty. The heavy wooden doors groan shut behind them, sealing them off from the roar of the rain, now muffled to a distant whisper. They step slowly forward, rainwater pooling at their feet as they place their bundles gently beside the doors.

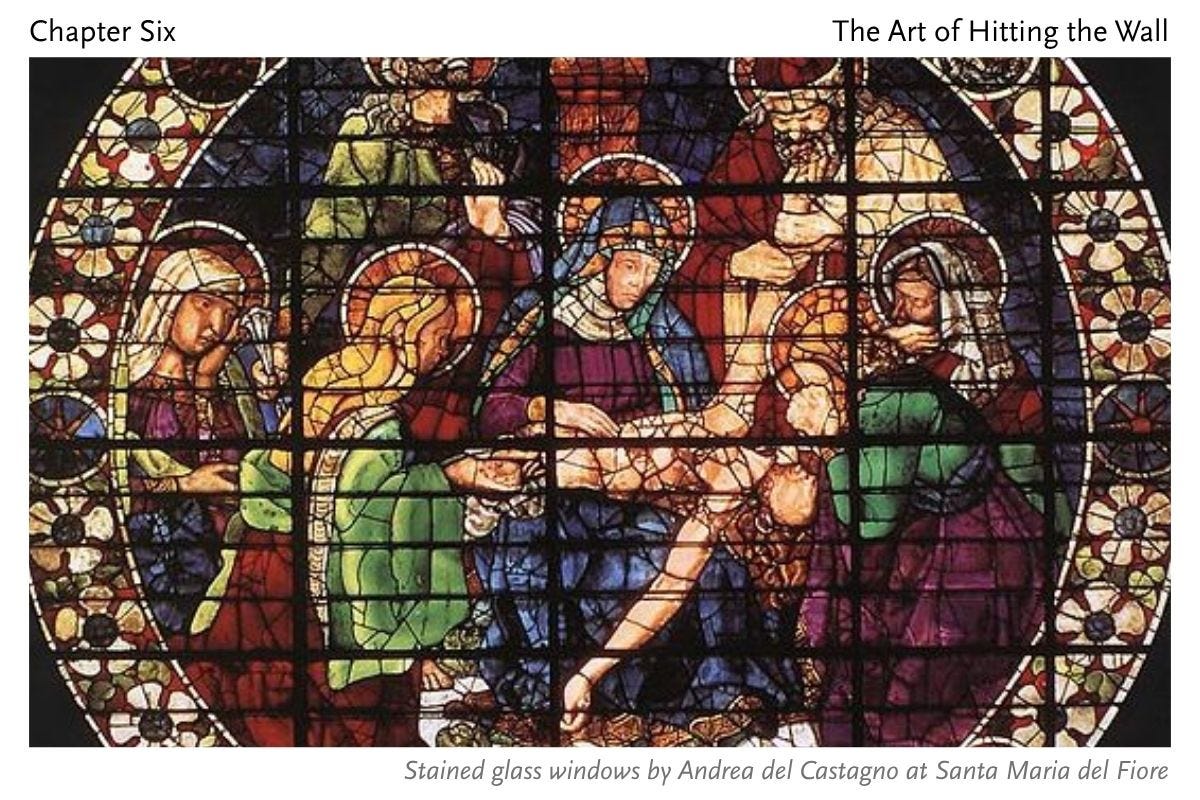

On either side, the tall stained-glass windows turn the storm’s deep blues and greys into the softest hints of amber and sage, rose and lilac, the colours changing with the light. The boys begin to make their way across the vast nave in silence, stone arches throwing shadows across the cavernous space.

The younger wipes at the nape of his neck, where a raindrop tickles him, his fingers still stained green from grinding malachite into pigment, for the painters.

The older, Piero, notices first, that their shadows have split, fanning out around them like the segments of an orange. He whispers to the younger, Niccolò, pointing. Two eyebrows lift in amazement as the younger boy looks around him, his face widening into a wonderous grin. Lifting his arms, he begins to spin around clumsily, feet stumbling across the patterned tiles, making the shadows whirl around him.

A burst of laughter escapes from Niccolò, sudden and bright, his head tipping back, the sound echoing around the room. But when he looks around, he sees that Piero has already moved onward, so he abruptly halts, teetering, patchwork tiles spinning for a moment longer, before he turns, racing to fall back into step with his older brother.

They are halfway to the altar now — two tiny figures adrift in a sea of endless marble, cold beneath the thin soles of their boots.

And then they can hear it in the distance, the continuous heavy slap of rain striking stone, getting louder now, echoing.

Directly ahead, where the transept cuts from left to right across the nave, and the lines of the cathedral meet, a curtain of rain falls in long, vertical threads, as if heaven were pouring itself directly into the earth.

Piero knows this is the place where any other cathedral would carry a dome of masonry, but he has only ever known this one — where the great mouth of Santa Maria del Fiore stands open to the sky, receiving the storm.

The air is cooler here, and the light has changed, too — stormlight spilling across the wet marble, in deep shifting shades of blue.

The boys step carefully now, deliberate. Niccolò inches forward, his boots slipping slightly as he leans just far enough to glimpse a crescent of storm-dark sky. The cold wind swirls, whistling faintly as it echoes off stone. Already, he can feel the fine spray on his legs, and he hangs back, shivering.

Piero stands before a silver veil of rain, his mouth pressed into a hard line. He draws a breath, bracing himself, then pushes through the cold shock. Niccolò watches his brother’s form vanish, becoming a vague silhouette, barely visible through the silver.

Rain lashes at Piero, shocking and clean. He shivers, walking on — ten steps, then twenty. The space is larger than it seems. He presses on until he is far out into the open heart of the cathedral.

They say the dome must be covered — everyone says it — but Piero can't imagine it, a space this wide, covered in masonry. More than that, he wonders why go to all that trouble, to build an impossible vault and paint it with angels when he can look up, now, and see straight into the heavens. Lifting his face to the sky, rainwater stings at his face, striking to blur his vision. He wipes his eyes, looking up again into the clouds above, churning, and heaving in a cauldron of grey.

“Perhaps a dome might be better” he thinks.

Grinning now, he turns, looking back towards his brother, but can’t see him through the thick curtain of rain. He calls out, but his words are washed away.

Piero heads back, now, shoulders hunched, blinking against the wet. The boys collect their tools by the door and later, when the downpour subsides, they slip back out into the square.

Behind them, the great cathedral remains.

She has stood like this for more than a hundred years — complete but for an open sky for a dome, since before their parents’ parents were born.

Imagine the rivers of rain she has swallowed, only to pour them back into the streets, racing to join the Arno again.

All across Italy, cathedrals had been rising — in Pisa, Siena, and Milan.

And Florence, never one to be outdone, had set out to build a cathedral worthy of her status. The dream had begun more than a century before. Her foundations were Gothic, the first stone laid in 1296. And stone by stone, she had been rising.

Then came the plague.

In 1348, the Black Death swept through Florence like wildfire, tearing through the streets in the span of a single season. Between the months of March and July —

that summer when the bells would not cease their tolling for the dead — half the city was gone.

Work slowed, and then stopped entirely. For a time, it seemed the city might never recover. But Florence did what she always does — she endured.

Now it is 1401.

The nave is finished, the tiles are laid, and light streams in through the coloured glass.

And at the heart stands an octagonal drum — eight sides of white and patterned marble, waiting to be crowned with the greatest dome the world has ever seen.

But somewhere in a back room, even the model’s dome has collapsed — a bad omen.

And still, she waits.

This is not a question of money.

Florence is wealthy, prosperous, and powerful. Her influence stretches across Europe.

Flying buttresses could do the job — but they are not the way of Tuscany. A row of crutches lined up along the outside? That might do for the French, or the Germans, perhaps. But Florence remembers her Roman ancestry, her lines are to be clean, and elegant. No external braces to support her from the outside. No internal arches to interrupt the perfect roundness of the choir vault on the inside.

She would rather be perfect and unfinished

than compromised now.

Instead, she would be like an old maid who has sent all her suitors away.

There is another problem, too.

A dome must be supported as it is built — held by a great wooden arch of scaffolding, bearing its weight until the structure, built, can bear itself. But to build a dome of this size would require a mountain of timber scaffolding. If they felled every tree in Tuscany, it still would not be enough.

The city moves around her, the wool merchants and goldsmiths, painters and sculptors, bankers and architects, all going about their work.

But now and then, when someone asks a question:

“Have the merchants had any trouble reaching Cairo with all this weather?”

“Do you think the price of wool will hold through the winter?”

Just for a moment, their eyes slip upward, unconsciously, up to the unfinished drum, floating above the terracotta roofs.

As if the answer might be there, found suspended in the negative space.

The cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore waits, her shape too vast to complete with the tools of the day, or the thinking they’ve inherited.

She is waiting, instead for a new kind of thought to arise.

Image Credit:

Stained glass windows by Andrea del Castagno at Santa Maria del Fiore

Didn’t want that to be cut short, very curious as to what those youngsters were up to and how you take that forward