Chapter 3: The Birth of Venus

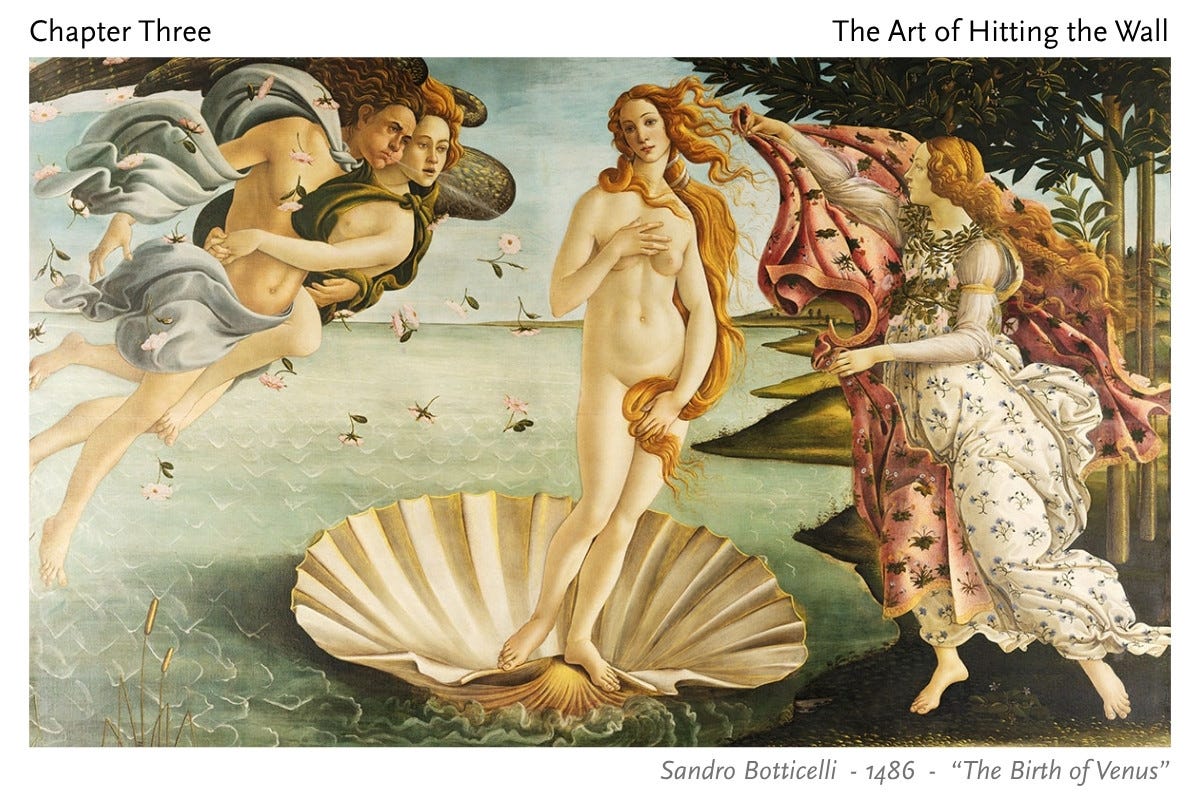

She floats toward us silently, across the surface of the sea, standing lightly in the hollow of a scalloped shell, as if gravity itself had granted her grace from its pull. Her skin seems lit by an otherworldly light that knows no shadow.

You know her.

She is Venus, Greek goddess of love and beauty, and as she arrives on the shore, she is welcomed by Hora, goddess of natural order. Her arrival is celebrated, as if the whole world had been holding its breath for her.

In the colors of a dream — seafoam green, blush rose, and shell white — the painting feels like memory rather than life, as though Botticelli painted not what he saw, but what he longed for.

I was standing in front of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, in the spring of 2010. The painting was somehow both bigger and smaller than I’d imagined, because in my mind, it wasn’t a painting at all.

It was the symbol of an era1.

Every wall and pillar was hung about with heavy, gilded frames. And all around me, I could feel the invisible influence of the Medici family — tied to every painting, every sculpture. Even we tourists seemed to hang on their strings as we shuffled from masterpiece to masterpiece in those high-ceilinged rooms, bathed in a soft light that could hold time suspended.

Low murmurs of reverence mingled with the echoing of footsteps, and then at once, all sound vanished as I stood face to face with Venus herself, taking in the delicate paint strokes, the details on Hora’s dress, the blossoms caught on the wind. And I felt a strange pull, then — a tugging at my thoughts, calling me away. I couldn't help it — I was looking at Venus, thinking, "Where is the Primavera?" I have always thought of these two paintings as sisters, and now that I was looking at the one, I could feel the invisible tug of the other.

I turned.

My mother was smiling her faraway smile, impossible to know what she was thinking. She was draped in tags and lanyards — we all were — to identify which tour group we had come with.

My little brother, Dylan, only nine, was indiscriminately scanning the whole room at once, wide-eyed, and overwhelmed by all the gold, the marble, and all the haloed saints.

And then I saw it — partially obscured by a row of tourists, across the room: It was Botticelli’s Primavera. She was here, too — of course she would be — in the same room, the two paintings holding a conversation across centuries.

I feel that if you look at the Birth of Venus out of context, you might miss Botticelli’s trick. It’s like seeing a painting of the moon by day. I have long thought that you need to first set your eye on the dark canopy of the orange grove in Primavera, where the figures are lit as if by an inner light, impervious to the shadows around them. Impenetrable.

Only then, when you look at Venus again, you see the radiance.

She glows.

In Botticelli’s hands, the boundary between myth and religion blurs: He was weaving the Virgin Mary into his idea of Venus, floating toward us like a blessing, with sea-spray tousling her golden hair.

We’ve stepped out into the courtyard now, eyes adjusting to the mid-afternoon light.

I press forward, following a floating head of cropped dark hair beneath a wide-brimmed hat as it bobs and weaves through the cobblestone streets of Florence. Our tour guide. She fields questions with the practiced ease of someone who has answered them a thousand times before. Her smile is quick, her gestures animated. Her enthusiasm is all for the crowd, not for the wonders themselves.

Earlier that day, I remember standing in the grassy Field of Miracles, in Pisa; looking up at the Leaning Tower. The clouds had been rolling overhead, thick and heavy with the threat of rain, painting an impossible marbled sky of crisp white, deep blue and dark grey.

I had been under a different kind of spell that morning. Instead of soaking in the details of the tower in front of me — with its intricate repeating lacework; the pillars catching the shifting light and shadows pooling in the arches — I was angling my camera this way and that, absorbed in the search for the ‘perfect angle’. I was trying to capture that other leaning tower — the one that I had seen in other people’s holiday photos. I thought I had almost captured it.

But as we climbed back onto the bus that would take us from Pisa to Florence, I realised my mistake as a flush of regret rose up in me — and a pang of shame. I had spent a year saving for this trip on my tiny salary, relishing every peanut butter toast dinner, savouring the thought of the 10 days that I would spend in Europe. And here I was, seeing it through the lens of my camera, letting it slip by.

I reached my seat and sat down heavily, berating myself.

Dylan climbed into the seat beside me. With all the cool composure of a nine year old, he scanned the other passengers boarding the bus, adjusted the straps of his camera, and switched it back on to check the battery level. I wondered what he would remember of this trip. When he’s older will he say “Oh, yes, I’ve seen the statue of David in Florence, The Sistine Chapel, The Sagrada Familia in Spain. I saw these things when I was young, and besides, I can look them up on the internet, can’t I?”

Or perhaps, when he is older, he will look at every photograph with a sense of half-recognition, asking “have I seen you once before, in real life?” Maybe he’ll look closely, hoping to catch a memory, searching old monuments like the faces of old friends.

Instead I worry — he’s missing out on the longing. For me, it is the longing that was beautiful — poring over artworks in black and white on cheap printer paper, relishing even a glimpse of color. Even those, ghostly images projected onto the whiteboard of a classroom. I learned to stretch the colors out in my imagination; to make them last.

I look at him, my eyes forming the question.

He turns to me, then, and says: “Oh my gosh, can you imagine if the leaning tower fell over right now, just as our bus was leaving?” And we both laugh.

In Florence, September’s sun is gentle with only a thin scattering of clouds. The breeze carries snatches of French, German, and Cantonese. There are bursts of camera flashes as we approach a particularly pretty spot. To my right, a woman gathers her family for a photograph, the river Arno as their backdrop. Arms raised, she is orchestrating the moment and as the camera clicks, I see a wave of relief pass over her face as one more memory is safely recorded.

The crowd begins to thicken as the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore comes into view in the heart of the city. From a distance, the huge marble blocks seem mostly white, luminous in the sun, but as we draw closer, the colours begin to reveal themselves, subtle threads of green and terracotta. The mid-afternoon light slants across the facade, setting off a faint rose tint that collects in every carved detail, giving the stone a blush of Tuscan sunset. I turn, squinting, to look into the sun, but it’s still riding high in the sky. It’s a clever sleight of hand, baked into the marble by the builders.

As we step into the enormous shadow of the cathedral, the heat drops suddenly away, and the facade rises like a patchwork quilt into the sky. I make my way to the edge of the cathedral, and Brunelleschi’s immense dome soars into view, capping the cathedral and floating above the city’s red roofs — a red rose in the skyline of Florence.

I try to hold onto the magic of this moment, but the crowd presses in — tourists speaking in a dozen languages, camera flashes, smartphones and a hundred little clues that it’s 2010.

Dear Reader, we’ve reached the place, but the Florence I wanted to show you isn’t here. She has receded into the centuries between then and now.

The real city — the one where this dome rises, not from these cobbled streets, but out of the very soul of the Renaissance — has vanished beneath the press of this crowd and the noise of the present.

To find her, we have to go back 600 years.

Back to 1401.

Image Credit: ‘Birth of Venus’ by Sandro Botticelli, Florence 1486, and ‘Primavera’ (Spring) by Sandro Botticelli, Florence 1482.

A note to my fellow lovers of art history:

Much of what I write here reflects my own way of seeing. I am drawing personal meaning from these works rather than presenting a textbook account. Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is perhaps not the most representative example of the Renaissance as a whole, but certainly of the Early Renaissance. The forms are softly elongated, and the precision of linear perspective that would come to define the High Renaissance has not yet fully arrived.

Good memories rekindled , proud to have experienced them, with you. Camera’s definitely store the memories but reduce the moment.💕

That is so beautiful, what a scrumptious read, I love the way took us back into ages past…. That’s what we all forget… I love it 🥰